Who Owns 1971?

If 1971 is to remain meaningful, it cannot be owned. It must be debated, carried with care, and opened to complexity. Otherwise, the Liberation War risks becoming either a party banner or a demolition tool. In both cases, the injury is the same: a past turned into a weapon rather than a shared ground on which a plural future might be negotiated.

It is academically problematic to categorize “Bengalis” as a single, anti-establishment bloc. The category is too deeply entangled with class, region, gender, party affiliation, and patronage networks to sustain such a claim.

Yet, when our political history is read with a critical eye, a recurring pattern becomes visible.

Power in this land repeatedly concentrates at the center and then projects a narrative of order, loyalty, and progress onto the periphery.

In response, time and again, the margins answer back, not always in the same language and not always with the same ideals, but through a shared refusal to take the center’s grand narrative for granted.

Our history, then, can be understood as a long and continuing argument over what constitutes a shared past.

I am aware that history is never apolitical. It always invites debate and controversy, producing multiple versions of the past.

However, the center has consistently promoted a version of history that appears to strengthen nationalism and national unity while often masking its deeper objective of ensuring legibility.

It seeks to turn the periphery into an orderly mosaic that is taxable, governable, predictable, and grateful, collectively producing a homogeneous map that reflects a single political ideology.

The periphery, by contrast, often survives through opacity and improvisation.

It resists not only specific policies but also the center’s authority to define what is normal, what is civil, what is modern, and what is national. When the center labels a demand as disorder, the periphery may interpret it as dignity.

When the center celebrates a project as development, the periphery may recognize it as dispossession. These are not merely differences of opinion; they represent competing regimes of truth.

This dynamic helps explain why our major political movements, when placed side by side, often resemble variations on a single theme. Motives and ideologies can certainly be debated, but the overall direction remains strikingly similar.

The center asserts hegemony, while the periphery produces counter narratives in response.

The struggle is not only over resources and political offices, but also over recognition, moral worth, and political voice.

Even the demographic and religious history of the Bengal delta can be revisited through this lens, though care must be taken not to reduce complex processes of conversion, migration, and social change to a single cause.

Still, it is significant that frontier zones and agrarian margins frequently became spaces where state authority was weak and where alternative moral communities could take root.

It is widely noted that the 1872 census surprised colonial policymakers with its findings on Bengal’s demography, findings that were later used by the colonial administration to deepen religious divisions between Hindus and Muslims.

Yet it is reasonable to assume that the census merely quantified a social landscape already shaped by unequal power, uneven land relations, and competing claims over identity. In this sense, the numbers arrived late to a story the villages already knew.

Look at the images that continue to haunt our political imagination. The Baro Bhuiyans governing beyond the easy reach of Delhi’s imperial discipline.

Titumir’s Bamboo Fortress confronting the British colonial administration, not merely as a physical structure but as an argument built of earth and reeds, asserting that the peasant frontier could imagine its own sovereignty, even though one version of history reduces it to religious orthodoxy.

Haji Shariatullah’s reformist resistance is similarly read as religious revival, yet it is equally legible as a critique of extraction, hierarchy, and the everyday humiliations sanctioned by those closer to state power.

These were not identical projects. Yet each marked a moment when the periphery refused the center’s monopoly over legitimacy.

Resistance in our history has never worn a single uniform. At times it speaks in the grammar of religious orthodoxy, seeking moral order against predatory power. At other times it speaks in the idiom of progressivism, demanding rights and dignity in the name of equality.

In some moments it rises as a struggle for freedom of expression, insisting that speech itself cannot be licensed by the state. At still other moments it appears as political rivalry, the everyday contest over who controls institutions, land, and patronage. The costumes change, but the stage remains.

This is why it is naïve to ask whether the periphery is always virtuous or the center always villainous. We must also be careful in defining what we mean by center and periphery. These are not merely spatial categories separating capital from hinterland.

Rather, they describe a political relationship between those who claim the authority to govern and narrate, and those whose voices are reduced to spectatorship. The issue, then, is not moral purity but structure.

The center depends on producing consent through narratives that naturalize its dominance.

The periphery disrupts that naturalization, sometimes with vision, sometimes with fury, and sometimes by turning the center’s own language back against it.

Our political reality is forged in this friction, where official stories collide with the stubborn memories of those expected to live within them.

The center builds its hegemony like a road laid across wetlands. The periphery responds like water: it bends, it leaks, it floods, and it finds another route.

To understand power politics in Bangladesh, I do not treat conflict as a temporary disruption of an otherwise stable order. Conflict is the order. Politics here is shaped by which narrative prevails at any given moment.

Yet, truth be told, over the last fifteen years I have rarely seen sustained, everyday engagement with 1971, the nation’s foundational historical event that officially anchors state nationalism, among ordinary people outside the circuits of power.

What circulated most loudly under the dominance of the then ruling and now ousted Awami League was not experienced by the majority as living memory, but as proclamation.

The narrative arrived with the confidence of authority, less an invitation to remember than a demand to agree.

Many learned to treat it as a collection of grand statements wrapped in the language of power, something to endure rather than internalize.

Regrettably, the script continues to be written in a similar style in the post August political order. The political shifts of August 2024 opened a crude competition over the past on which the country’s very foundation rests.

Those newly sheltered by central power began to question the Liberation War and the meaning of independence, as if history were a property to be re-registered under new ownership.

Yet here again, the periphery has resisted these new narratives, particularly those receiving direct or indirect endorsement from the center.

I have observed a renewed popular interest in the history of the Liberation War and in the actions of political leaders from that period.

Many who appeared indifferent under the previous regime’s narrative of 1971 reacted sharply when they sensed that their moral and civic identity was once again under threat.

In James Scott’s sense, this response resembles everyday resistance, a quiet but firm refusal to allow the center, old or new, to monopolize the authority to define the nation.

A new group has attempted to impose its own version of history in order to consolidate power, while the center has indirectly patronized this effort through silence or implicit endorsement.

This includes statements framed as personal opinions and circulated through social media by influential individuals widely believed to be closely associated with the interim government.

This development should not be read simply as partisan rivalry. Rather, it reflects a conscious effort to revise history for the purpose of consolidating power under the guise of decolonization.

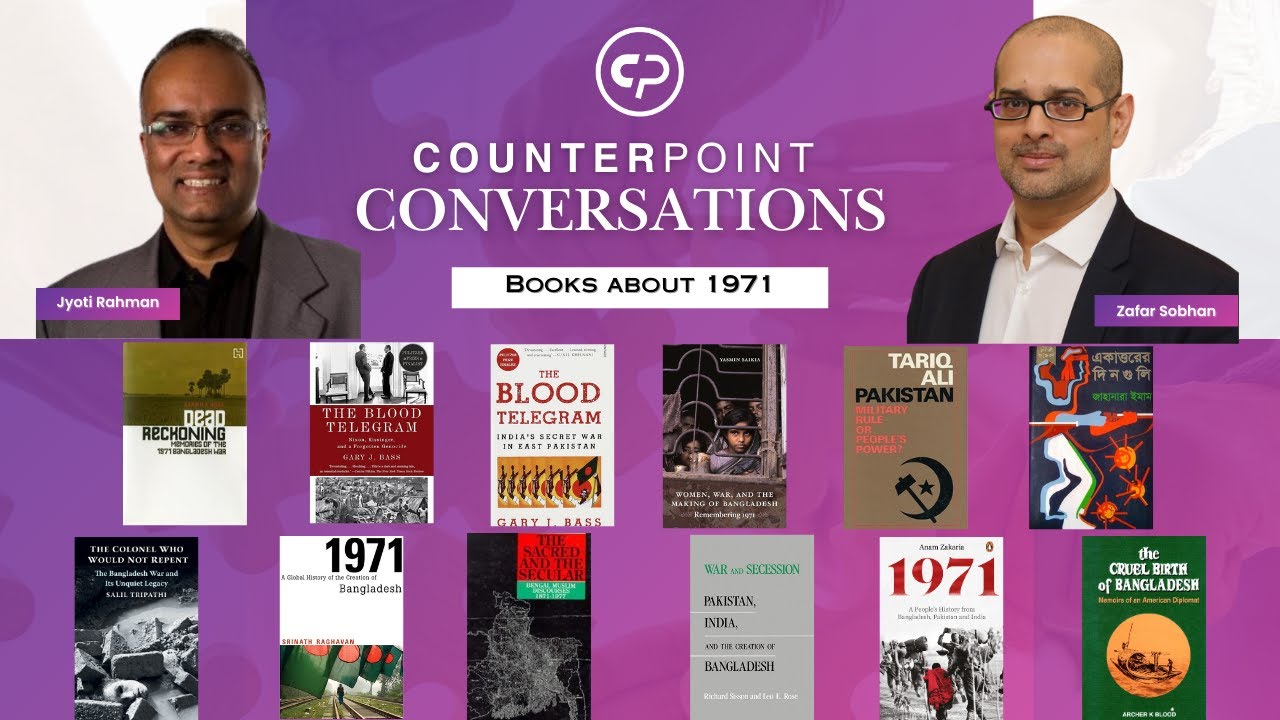

Decolonizing history is a long and demanding scholarly task, and in Bangladesh it requires a difficult but necessary separation.

The Liberation War must be freed from the proprietary claims of any single political party. It must be returned to the people as a shared archive of sacrifice, fear, courage, and fracture.

However, if this process turns into an attempt to erase Sheikh Mujib’s political leadership before and during the Liberation War of 1971, or to deny the role of the then Awami League as the party that called for resistance against Pakistan, this is not decolonization.

It is an attempt to recolonize history through subtraction, replacing one monopoly with another.

Once such recolonization begins, a further irony emerges. Those who weaponize denial today may, in time, revive the very party they claim to oppose, because the politics of history often swings back like a pendulum in search of an anchor.

I know this is not easy. The Awami League has built its political identity around 1971, or more precisely, it has long manipulated the history of independence to legitimize nearly seventeen years of authoritarian rule.

Over time, the Liberation War itself became folded into the party’s self-definition.

This has created a widespread fear that to speak seriously about 1971, or to resist the fashionable skepticism now surrounding it, is to hand political advantage back to the Awami League. Yet this fear misreads both history and politics.

When history is treated as a tactical instrument, it ceases to function as a shared commons and becomes a battlefield of competing scripts.

In such moments, history itself turns into a form of everyday resistance, not because people suddenly become historians, but because they refuse to be governed by manufactured forgetting or by manufactured histories presented as fact.

For years, the Liberation War was deployed as a shield in partisan politics, a moral passport used by the Awami League to foreclose criticism and consolidate authority. The outcome was predictable.

Ordinary people resisted an official version of the war that was fenced off from debate, complexity, and contradiction.

After the collapse of that fenced narrative, a counter narrative has begun to emerge. This development, however, carries its own dangers.

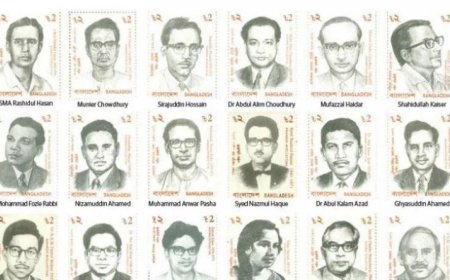

When the past is rewritten primarily to punish opponents, it becomes another divisive craft, driven more by resentment than by inquiry. This is why Sheikh Mujib cannot be read as a single, unchanging figure.

The Mujib of 1966, the Mujib who emerged as the majoritarian leader after the 1970 election, the Mujib of March 7, 1971, the imprisoned Mujib who remained a symbolic center throughout the Liberation War, and the Mujib of 1975 are not the same political subject.

History does not move in a straight line, and neither do political leaders. To compress Mujib into a single portrait is to turn a living archive into a stone idol, whether that idol is constructed for worship or for demolition.

The Mujib of 1971 must be granted his due as the political leader of a moment of collective rupture. At the same time, criticism of the constitutional failures and authoritarian tendencies associated with 1975 is a legitimate part of historical reasoning.

What is not legitimate is the erasure of one achievement by weaponizing another failure. That move amounts to recolonization through replacement, and people resist it because they recognize the technique even when the actors change.

If 1971 is to remain meaningful, it cannot be owned. It must be debated, carried with care, and opened to complexity. Otherwise, the Liberation War risks becoming either a party banner or a demolition tool.

In both cases, the injury is the same: a past turned into a weapon rather than a shared ground on which a plural future might be negotiated.

As a self-proclaimed nonpartisan authority, the current interim government occupied a rare political opening. It could have decolonized public memory, not by replacing one monopoly with another, but by restoring historical plurality.

In other words, it could have de-Awamified history.

Such a project, however, required disciplined sequencing. It would have had to begin by acknowledging Sheikh Mujib’s role in 1971 and the political leadership of the Awami League during the Liberation War.

Only then could it have credibly moved to the second task of exposing the later decline of Awami League leadership and holding the fallen fascist regime accountable through transparent and rule-bound processes. Instead, what we witnessed was a lopsided posture.

There was apathy toward the first task and selective enthusiasm for the second. This imbalance reveals a familiar weakness of the center.

It does not know how to confront the Awamification of the Liberation War without either surrendering the past to a party or attempting to expunge it from history altogether.

If the head of government publicly recalls Mujib’s role in 1971, that act does not automatically grant the Awami League any political advantage.

It can instead function as a gesture of civic honesty, a minimal recognition that allows the national narrative to breathe beyond party property lines.

Yet over the last year and a half, no such attempt has been made by the interim government. Even during March and December, two months deeply embedded in the memory of the Liberation War, the government’s unease has been evident.

The head of the interim government, Professor Yunus, acknowledged Major Zia, one of the key figures of the Liberation War who declared independence, yet he did not utter the name of Sheikh Mujib, under whose political leadership and on whose behalf that declaration was made.

The contradiction is striking. Military leadership was recognized, while political leadership was rendered invisible, even though the interim government’s primary mandate is to guide the nation through political transformation after a prolonged period of authoritarian rule.

The political risk, then, does not lie in acknowledging Mujib. It lies in refusing to do so. When the state avoids this acknowledgment, ordinary people begin to ask questions that go beyond party rivalry.

Is the Liberation War the exclusive inheritance of the Awami League? Can others claim the history of independence without passing through the party’s gate? Who has the authority to authorize national memory?

These questions do not signal confusion. They mark the re-entry of politics into history itself. Returning to James Scott, such questioning functions as a form of everyday resistance, a refusal to allow the center to regulate belonging by regulating remembrance.

What is striking is that this resistance is not produced only by opposition forces. It is generated by the center’s own mismanagement of memory. When power treats history as a tool, it invites suspicion.

When it treats recognition as a concession, it turns basic facts into contested terrain. In attempting to escape Awamification through omission and silence, the interim government risks creating a paradox.

The more it tries to detach the Liberation War from one party without confronting its history honestly, the more it reinforces the perception that 1971 remains party owned, because even the state cannot speak it plainly without fear.

There is a common saying: “We learn from history that we do not learn from history.” In Bangladesh, the sharper lesson may be this: When the center governs memory as if it were a ministry, the periphery begins to remember as if remembrance itself were a form of political action.

Dr. Mohammed Abdul Baten is a faculty member at North South University. The views expressed in this article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of his institution.

What's Your Reaction?