The True Story of December 16, 1971

On this day, Bangladesh did not yet know what it would become. It only knew what it had endured. The newspapers recorded surrender, denial, diplomacy, return, and rebirth. The people carried something else entirely -- a heavy, wordless knowledge of survival. That knowledge, more than any headline, is what remains.

On this day in 1971, the war did not end cleanly. It thinned, frayed, and overlapped with itself. December 16 did not arrive as closure. It arrived as simultaneity -- surrender and denial, relief and terror, truth and propaganda all claiming the same date.

From a distance, the language was decisive. Pakistan accepts surrender. The words appeared in bold type in international newspapers. Generals were named. Ultimatums acknowledged. India would send a general to Dacca. Bombing of the capital had been halted. The end, the world was told, was procedural and imminent.

Closer to the ground, the day felt unfinished. Reports still described East Pakistan’s situation as critical. Civilian areas were being bombed even as surrender was discussed.

Children were killed; others were wounded. The war, it seemed, had not yet been informed that it was supposed to stop.

In Dhaka, silence did not reassure; it unsettled. After nine months of bombardment, quiet felt tactical, temporary. Radios stayed on, turned low. Doors opened cautiously. People did not ask: Is it over? They asked: Who controls the night?

In New York, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto walked out of the United Nations Security Council in tears, denouncing the body before leaving in visible distress. The image would become emblematic of defeat.

But in Bangladesh, it landed without ceremony. Tears had long since lost symbolism. Crying had become private, almost redundant. What mattered was not the humiliation of a foreign minister, but whether the machinery of killing would finally stop.

That same day, uncertainty deepened with the movement of distant powers. The United States dispatched an aircraft carrier to the Bay of Bengal, officially for evacuation and humanitarian readiness.

Unofficially, it reinforced a lesson Bangladesh had learned painfully: even its ending would unfold under the gaze of others.

Pakistan, meanwhile, sought guarantees. Safety for prisoners of war. Protection for minorities. Assurances against reprisals. The language was careful, legalistic.

Yet those reading these appeals remembered villages erased without warning, humanitarian symbols violated, uniforms acting without consequence. Safety, to them, was not a clause -- it was something already withdrawn.

In the Bangla press published from Kolkata, the day was recorded differently. Weekly Bangladesh wrote of tensions within the Bangladeshi leadership -- disagreements sharpened by exhaustion and pressure.

But the emphasis was not on fracture. It was on Tajuddin Ahmad’s political discipline, his ability to hold together a provisional government and translate resistance into governance. Victory, the paper suggested, was not accidental. It had been argued into existence.

Other writers speculated about Pakistan’s future after December 16. Would defeat produce reckoning? Would loss lead to restraint? The question was asked earnestly. History has since answered it.

Pakistan did not learn. It converted loss into grievance rather than accountability. But on that day, the future remained unresolved.

There were also questions about Bangladesh itself. Would the newborn nation be recognized at the United Nations? Would sovereignty be welcomed or merely tolerated?

Independence, these writers understood, was not complete at the moment of military victory. It required admission, naming, acknowledgment.

The Daily Bosumoti captured the confusion of the moment. Yahya Khan was reported to have instructed General Niazi to surrender, even as uncertainty persisted about what was actually happening in Dhaka.

In the western front, fighting continued. Planes were shot down. Tanks destroyed. Geography refused to align with diplomacy.

In The Daily Jugantar, surrender appeared not as a headline but as a process. Niazi was reported to have begged India to stop the war; the reply was blunt: surrender first.

Roads into Dhaka had been cleared by the Mukti Bahini. Pakistani troops abandoned vehicles as they fled. Paratroopers were captured. Collaborators were arrested. Towns like Bogra were declared free -- not ceremonially, but factually.

Alongside war’s end, life edged back in. Tens of thousands of refugees crossed homeward. The government of Bihar announced that Bangladeshi refugee students would be allowed to sit for their board examinations.

A film -- Jai Bangla Desh -- began screening in Indian theaters. Culture, education, and ordinary aspiration returned before justice had even been defined.

There were gestures that carried particular moral weight. Colonel M. A. G. Osmani, commander-in-chief of the Mukti Bahini, was reported to have paid respect to his Indian schoolteacher.

In a landscape saturated with death, this act mattered. It suggested that war had not erased gratitude, lineage, or humility.

Abu Syed, a Bangladeshi envoy, addressed the international community and announced the birth of a new nation. The declaration was sober, restrained. Birth, after all, is painful. This one had been prolonged far beyond endurance.

International journalists crossed into newly freed regions and reported what they saw -- burned homes, emptied towns, survivors emerging cautiously. Their dispatches offered hope to those still trapped in occupied areas, still being hunted.

For many, liberation did not arrive on December 16. It arrived later, or not at all.

Some discoveries darkened the moment further. Pakistani ammunition was found hidden inside a UNICEF vehicle. Even humanitarian symbols had been conscripted into war. Trust, once broken at that scale, would not be easily repaired.

And still, denial persisted. On the very day surrender was being negotiated, Pakistani newspapers ran pieces boasting of “air superiority.” The war did not end because its authors admitted failure. It ended because it could no longer be sustained.

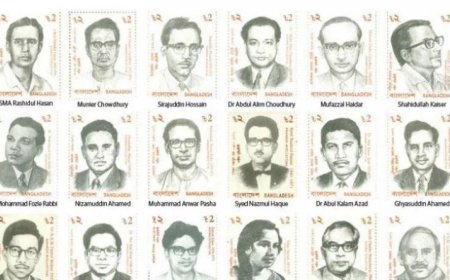

Justice hovered, unresolved. The expatriate Bangladeshi government spoke of holding Pakistani military personnel and collaborators accountable.

The language was firm but measured. Justice was framed not as vengeance, but as necessity. Even on the day killing seemed to pause, reckoning remained unfinished.

As night fell, there were no celebrations. People waited. They counted the missing. They imagined mornings without fear, even as fear lingered in their bodies.

Children wandered farther. Adults sat down -- not in joy, but because they finally could.

December 16 did not undo the nine months that preceded it. It did not resurrect the dead or answer the questions that would haunt Bangladesh for decades -- about memory, accountability, and who would be allowed to tell the nation’s story.

What it did was quieter, and perhaps more profound: it stopped the killing.

On this day, Bangladesh did not yet know what it would become. It only knew what it had endured. The newspapers recorded surrender, denial, diplomacy, return, and rebirth.

The people carried something else entirely -- a heavy, wordless knowledge of survival. That knowledge, more than any headline, is what remains.

Omar Shehab is a theoretical quantum computer scientist at the IBM T. J. Watson Research Center, New York. He is also an alumnus of the Shahjalal University of Science and Technology.

What's Your Reaction?