The Colour of Prejudice

It is often the person of colour who has to bring up colonialism in the room. To name racism even when it makes everyone uncomfortable. To remind people that representation is not neutral, and that curiosity does not absolve power.

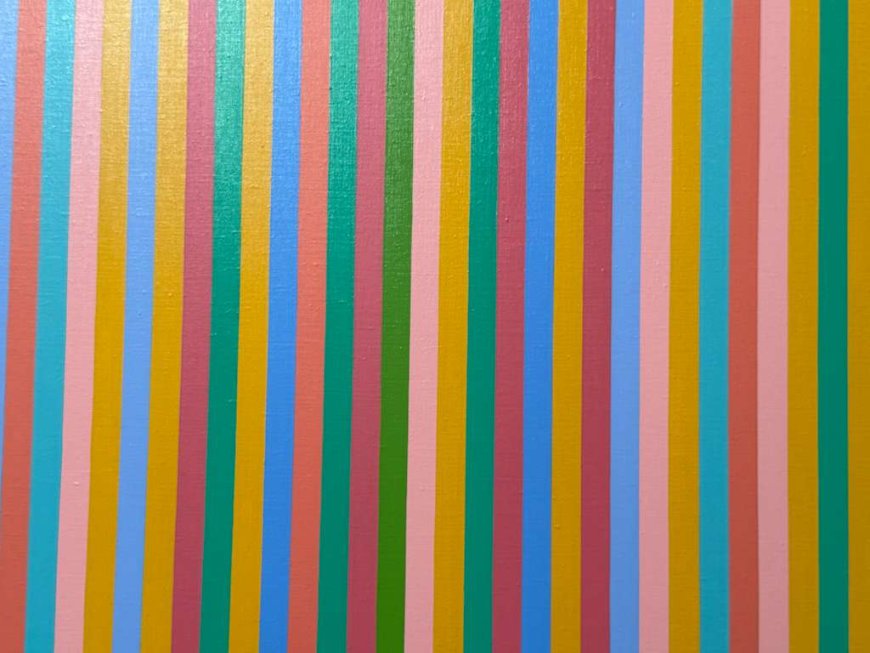

When I left Paris the last time, I felt an almost physical sadness. I wanted to be back. I wanted to return to the Musée d’Orsay and stand again before the straight lines of Bridget Riley, an artist whose precision is so restrained that it offers a strange solace to overwhelming emotion. Her work does not console through excess but through discipline. It holds itself together. I needed that.

Odeon Redon’s dreamy flowers, originally designed for the walls of a chalet, made me cry quietly. Their softness, their inwardness, their refusal to explain themselves felt like a permission to feel without being interrogated. I wanted all of this beauty. I wanted to be held by it.

And yet Paris is also a place that made me feel other things -- things that were uncomfortable, unresolved, and quietly violent.

I left home when I was seventeen. I crossed continents and the Atlantic to study at a women’s college in western Massachusetts. I left because I needed to get out of a box I had not yet fully named. Bangladesh, for all its intimacy and contradictions, felt too small for the questions I was beginning to ask. I wanted the world.

But with the world came something I had not yet encountered: Racism.

Growing up in Bangladesh, and traveling extensively from a very early age to Thailand, India, Singapore, and China, I had never learned to see myself as “other.” I was simply a person moving through places. It was only in America that I learned I was “brown,” that I was a “woman of colour,” that my body carried a history I was now expected to perform, explain, and sometimes apologize for.

I learned about the genocide of Indigenous peoples during my first Thanksgiving. I learned about slavery, segregation, and affirmative action. Perhaps this was because I went to a radical liberal arts women’s college, where a diverse group of professors insisted on historical context rather than comfort. For four years, my education was not just about literature or philosophy, but about understanding the social, political, and cultural conditions that create and sustain inequality.

America, for all its violence, also gave me language. It gave me frameworks. It gave me the ability to name power.

In my early thirties, I began working and traveling extensively in Europe -- for film festivals, development labs, financing and post production. I had access to public funding systems, to film financing supported by European taxpayers.

I learned that in Europe, there is still a belief in international cinema as an important cultural practice. One can make the films one truly desires -- films without obvious commercial hooks and still find distribution.

These subtitled films can play in theatres for months. This was unimaginable to me in Bangladesh, and increasingly rare in the United States. And yet, in Europe, I encountered another form of racism. Quieter. More suffocating.

It was as if every line from Edward Said’s Orientalism was being rehearsed in front of me. There was a gaze I had to learn to fight -- not only the male gaze, but the Orientalist gaze. A gaze that claims curiosity, but is structured by hierarchy. A gaze that registers only the slums of Dhaka as authentic and visually compelling Bangladesh.

European art history is deeply entangled with this gaze. The East has long been imagined as sensual, chaotic, impoverished, spiritual, excessive -- everything the West defines itself against. This logic has not disappeared; it has simply been aestheticized.

In contemporary European cinema and art spaces, Bangladesh is often legible only through poverty, suffering, and visible lack. After all, our work is categorized as “films from the South.” This essentialization is presented as realism.

One has to resist it, insist on complexity, interiority, and contradiction -- even at the cost of distributors and festivals silently categorizing such work as “less authentic.” As if dignity, desire, boredom, or abstraction are Western privileges!

Even my closest, well-meaning friends carry this gaze. We argue. We fight. We make movies together. Love grows. And I believe in this process cinema works through encounter. Film sets can open spaces for transgression and unlikely alliances.

And yet it is often the person of colour who has to bring up colonialism in the room. To name racism even when it makes everyone uncomfortable. To remind people that representation is not neutral, and that curiosity does not absolve power.

This is the paradox of Europe for me. It offers beauty, rigor, and public support for art. And at the same time, it asks me to remain legible within a narrow frame. It silently expects me to be grateful. To quietly accept my “otherness.” They are the norm; I, in my brown body, colonial history, and postcolonial reality, am the deviation. For example, in a restaurant, I must use a fork and knife; if I eat with my fingers, it draws glances.

I return to Bridget Riley’s lines because they do not ask me to explain myself. I return to Redon’s flowers because they do not demand meaning. Perhaps that is what I am still searching for -- a place, or a way of making art, where I can exist without being reduced. Without being translated. Without being essentialized.

A place where beauty does not come at the cost of erasure.

Rubaiyat Hossain is a film mentor, screenwriter, producer and director. She is a visiting faculty at Smith College where she teaches Gender, Film and South Asia Studies.

What's Your Reaction?