How Dhaka Kills Me Every Day

Dhaka is not for beginners. Every day you make it to the end in one piece is a good day. Even survival for another 24 hours is a victory.

You wake up in Dhaka, and the first thing you notice isn't birdsong or sunlight. It's the haze. That thick, gray curtain hanging outside your window that turns the sunrise into a vague orange smudge. You tell yourself it's fog, but you know better. Your throat already feels scratchy. You haven't even brushed your teeth yet, and your body is reminding you: another day of this.

Morning: The Pressure Cooker Begins

You leave at 6:40 AM because leaving any later means you might as well not leave at all. The streets before 7AM are deceptively calm, and it's the only time Dhaka pretends to be a normal city. But by 7:30, the transformation is complete. What was a road becomes a battlefield.

Getting to work isn't commuting, but surviving. You have choices, but they're all terrible.

Take the bus, and you're playing a game where the prize is finding a seat and the penalty is being crushed against strangers in a vehicle that smells like sweat, exhaust, and despair. If you're skinny like me, you have no defense except sarcasm, and sarcasm doesn't help when you're being shoved against a window that hasn't been cleaned in months.

Good luck trying to safely get on the bus in the middle of the road while a bike almost crushes you.

Or take the Metro. The "ultra-fast pressure cooker," as we call it. Yes, it's faster. Yes, it's cleaner. But calling it crowded is like calling a tsunami "a bit of water."

You don't get on the Metro during rush hour; you get absorbed by a human wave that carries you into the compartment whether you're ready or not. "The compartments are usually so tightly packed that you cannot even stand properly," and when you finally emerge at your stop, your joints ache from all the pushing and shoving.

Getting off is easy because the crowd ejects you like a sneeze.

Getting on requires abandoning any concept of personal space or dignity.

Then there's the leguna. These small public transports feel like they're held together by prayer and duct tape. The reckless driving, the seats designed for people half your size, where they somehow cram an extra person, the sensation that the whole thing will disintegrate at the next speed bump.

"It feels like it will fall apart at the next speed breaker," and that's not paranoia but an experience.

The Air That Becomes Part of You

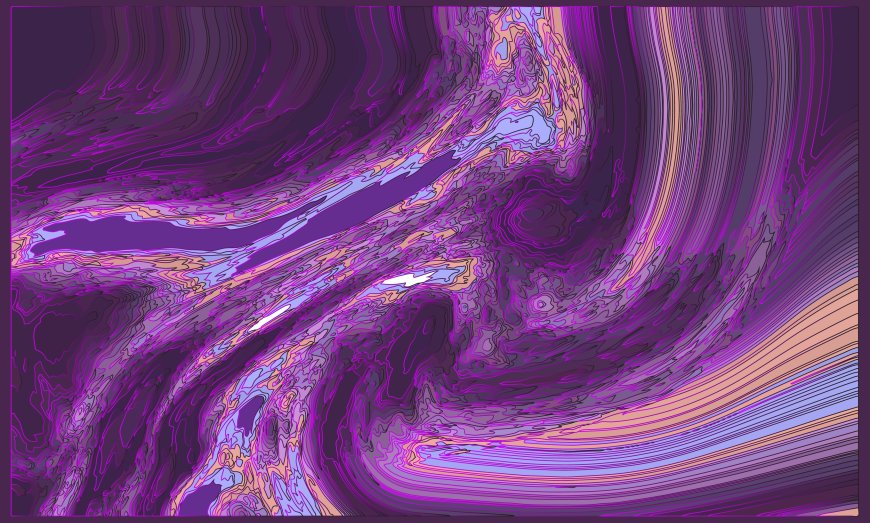

But the real killer starts the moment you step outside. The air doesn't just smell bad, but also has texture. It coats your throat. You can taste it. On October 27, 2025, Dhaka woke up to an AQI of 156, ranking sixth worst globally. But those are just numbers until you're the one breathing it. Every breath is 2.6 to 2.9 cigarettes.

I don't smoke, but my lungs don't know the difference.

The PM2.5 levels are up to 13 times higher than what the WHO says is safe. After a few months here, you stop noticing the cough. It becomes background noise, like traffic. You see children in school uniforms hacking as they walk to school, and nobody even turns their head. It's normal.

This is what normal looks like now.

My friend from Dinajpur can't stay in Dhaka for more than two months without getting physically ill. "Once I'm back in Dinajpur, I feel good. Both physically and mentally. I don't even need to get out of the house to feel good as the air quality does the job," they said. Sometimes I wonder what it's like to breathe air that doesn't hurt.

I've lived here so long I've forgotten what clean lungs feel like.

The Noise That Never Stops

And then there's the noise. God, the noise. Dhaka is the loudest city on Earth -- 119 decibels, louder than a rock concert, as loud as standing next to a jet engine. But concerts end. Jet engines fly away. This never stops.

Cambridge English couldn't teach me how to write descriptive essays, but Dhaka did. It's not just traffic. It's the honking -- the endless, pointless honking that communicates absolutely nothing except everyone's mutual frustration. Its construction starts before dawn. It's generators. It's the call to prayer from five mosques, all slightly out of sync. It's vendors shouting. It's buses grinding gears. It's motorcycles without mufflers. It's everything, all at once, forever.

You stop hearing individual sounds after a while. It all blends into white noise that makes your skull vibrate. You come home and your ears are ringing. You lie down, and the ringing doesn't stop. You wonder if this is what going deaf feels like, not silence, but a constant screaming in your head that you can't escape.

Welcome to my world of having tinnitus with extreme hearing loss, one that you can experience without even having the chronic illness.

You just had to live in Dhaka.

Looking Up Is Just As Dangerous As Looking Forward

Then you look up and see the wires. That insane, chaotic spider web of electrical cables that looks like someone gave a toddler a crayon and told them to scribble on the sky. They've been there for over a decade, despite court orders to remove them. Nobody follows the court orders. The cables stay. The transformers wrapped in wires stay, threatening to explode every time it rains. There are instances where the situation has changed, like in Sylhet, where they redirected every cable underground. But oh well, who's gonna do that to Dhaka, right?

In May, two people died stepping into puddles that had live wires in them. Just regular puddles after regular rain. Step in the wrong one and you're dead. There's no warning sign. There's no way to tell which puddle is safe. You just have to hope.

I walk under those wires every day. I don't look up anymore because looking up means thinking about what happens if one falls. If the wind picks up. If the pole rots through. If someone does shoddy maintenance work, which they always do.

I just walk fast and hope today isn't the day.

Final Destination, Except It's Real

On October 14, sixteen people were burned to death in a garment factory because someone had padlocked the roof door with two locks. They didn't burn but suffocated on toxic gas from chemicals stored illegally next door. Most were teenagers, fourteen years old, working for less than 7000 BDT a month. One girl had complained to her sister the day before: "There's never a day off here". The next day, she was dead.

On October 27, a man named Abul Kalam was standing at Farmgate waiting, minding his own business, when a 140-kg bearing pad fell from the metro rail pillar above him. It crushed him instantly. He was 35 years old. He was just standing there.

I'm an avid cyclist who likes traveling. It's my cheap method of going to places unexplored. But Dhaka had different plans for me. A few weeks before, a CNG hit my bicycle, and I fell down, instantly dislocating my left knee. But the story does not stop there. Another CNG from behind went ahead and ran the vehicle into me, crushing my hand. The driver speeds away, and you're left bleeding on the pavement, if you're lucky enough to still be breathing. Also, yes, I'm typing right with the same hand. It hurts, but didn't we all go numb at this point?

Crossing a road in Dhaka requires calculations. You watch the traffic patterns. You wait for a gap that will never quite be big enough. You commit. You run. You pray. We have developed a sixth sense that allows us to make the intricate calculations that make us take a dash for it and cross the road. But what if someone does not have it? What if that person is disabled? Imagine yourself in their place, even for a second.

Please, close your eyes right now and do it.

There Is No Escape

Every morning, I wake up and think: here we go again. Another day of negotiating with death. Another day of inhaling poison. Another day of my ears ringing. Another day of dodging traffic and hoping the infrastructure holds, and praying that today is not the day a bearing pad falls or a wire snaps, or a puddle electrocutes or a bus doesn't stop.

Final Destination imagined death as a force that engineers elaborate traps. Dhaka doesn't need to engineer anything. The traps are already here, built into the infrastructure, woven into the air, suspended overhead in tangled cables, lurking in puddles, hurtling down streets at reckless speeds. All the city has to do is wait. Eventually, probability catches up with everyone.

And tomorrow, I'll wake up and do it all again. Because what choice do I have?

This is Dhaka. This is what kills me every day.

What's Your Reaction?