Why Minority Safety Is Essential for Fair Elections and Democratic Bangladesh

With the election scheduled to take place in the coming days, the need to heighten and strengthen protective measures is now immediate and critical. Preventive security, early warning, and community engagement efforts must be intensified not only on polling day but throughout the pre-election and post-election period, particularly over the next month, when risks of retaliation and intimidation have historically been highest.

In Bangladesh, elections are often described as moments of national decision-making -- occasions when citizens exercise political choice and the state renews its democratic legitimacy.

Yet for minority communities, elections, like other transitional political periods, have repeatedly been experienced not as moments of empowerment but as moments of fear, vulnerability, and exposure.

As Bangladesh approaches what is expected to be a participatory election after nearly two decades, anxieties among minority communities have once again intensified, regardless of the electoral outcome.

This persistent fear is not only a human rights concern; it poses a direct threat to the integrity and credibility of the electoral process itself.

This reality reflects a collective failure to build and sustain institutional mechanisms capable of ensuring the safety and dignity of minority communities during periods of political transition. The fragility and incapacity of institutions have become particularly evident during interim governance, when protection gaps widen and accountability weakens.

Recent incidents, including the killing of Dipu Chandra Das, have further deepened concerns and underscored how quickly insecurity can escalate in the absence of effective preventive measures.

These patterns demonstrate that minority vulnerability during elections is neither accidental nor isolated, but structurally linked to governance breakdowns during transitional moments.

Against this backdrop, a recent study conducted by Sapran -- Safeguarding All Lives serves as a critical early warning for relevant authorities. Drawing on two decades of data across multiple national election cycles, the study systematically examines patterns of violence targeting minority communities and maps district-level hotspots based on risk concentration.

Importantly, the analysis also incorporates recent developments during the interim period, revealing how risk geographies shift under political uncertainty. By identifying districts that are high-risk, moderate-risk, and structurally prone to violence, the study provides an evidence-based foundation for preventive action.

This study draws on archived reports from major Bangladeshi national dailies across multiple election cycles. Coverage for the 2001 and 2008 elections relied on Prothom Alo and The Daily Star, examining incidents reported in the ten days before polling, on election day, and in the ten days after. For the 2014, 2018, and 2024 elections, data were collected from Prothom Alo, The Daily Star, and Samakal, with additional monitoring of the interim period through Jugantor, New Age, and Ittefaq.

Each reported incident was treated as a single case and categorized by type of violence, affected community, electoral phase, and district. Mapping these incidents enabled identification of recurring hotspots and long-term patterns of election-related violence against minority communities.

The Hotspots

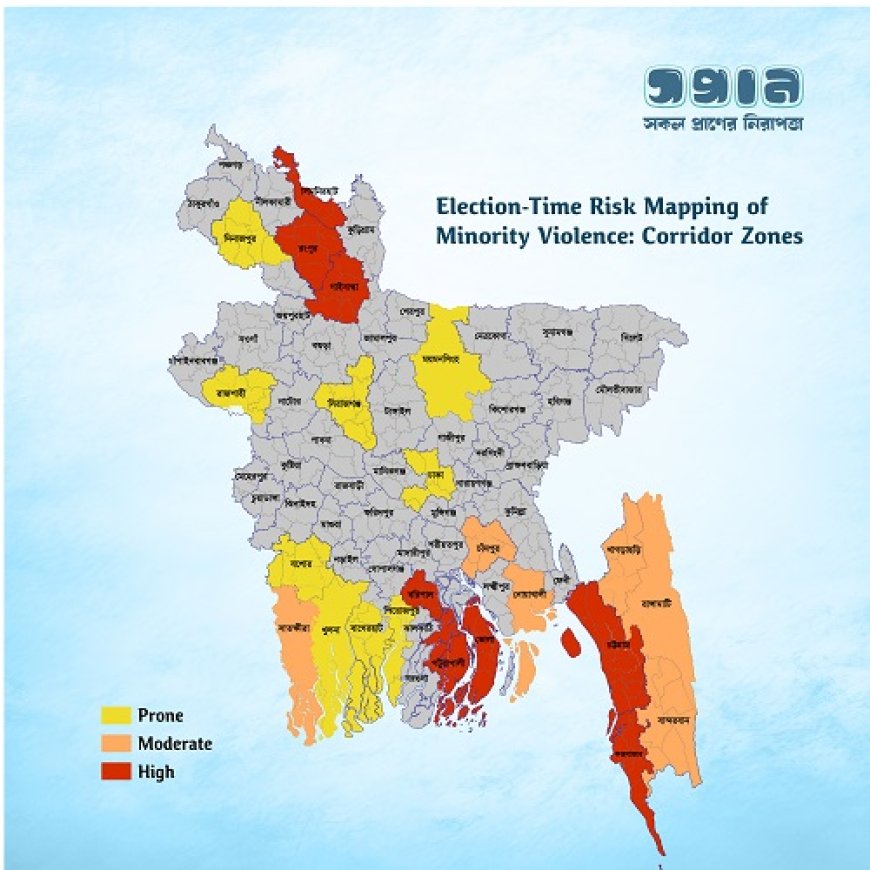

This choropleth map, developed by the Sapran team, visualizes the recurring geography of election-time violence against minority communities in Bangladesh, drawing on documented reports from national media across multiple election cycles between 2001 and 2024.

It highlights districts that have repeatedly emerged as sites of minority-targeted violence, reflecting patterns of frequency, recurrence, and structural vulnerability. The shading represents different levels of risk concentration: red indicates high-risk hotspot districts, orange marks moderate-risk areas, and yellow highlights districts that remain structurally prone to escalation.

Based on the early warning analysis, high-risk districts include Lalmonirhat, Gaibandha, Cox’s Bazar, Rangpur, Patuakhali, Barishal, Bhola, and Chittagong, where historical recurrence and recent escalation indicators converge.

Moderate-risk districts include Satkhira, Rangamati, Bandarban, Khagrachhari, Chandpur, and Noakhali, where tensions remain sensitive and may intensify in the absence of preventive measures.

Risk-prone districts include Mymensingh, Dhaka, Khulna, Pirojpur, Rajshahi, Sirajganj, Dinajpur, Bagerhat, and Jessore, which, while currently less concentrated, retain latent vulnerabilities rooted in past patterns of violence.

Two major risk corridors are clearly visible in the map. A northern corridor emerges around Rangpur and adjacent districts, reflecting long-standing exposure to post-election reprisals and land-related disputes, while a southeastern corridor extends across coastal and hill regions, shaped by overlapping pressures related to demographic change, indigenous land conflicts, and rapid rumour escalation.

The Same Districts Keep Reappearing

The repeated appearance of the same districts across multiple election cycles reinforces the conclusion that election-time violence against minority communities in Bangladesh is structurally patterned rather than randomly distributed. Districts such as Chittagong, Bhola, Barishal, Patuakhali, and Rangpur recur not simply because of episodic unrest, but because they combine several enduring risk factors: Significant minority populations, histories of electoral reprisal, contested land and property relations, and weak local accountability mechanisms.

Similarly, districts including Jessore, Bagerhat, Dinajpur, Sirajganj, and Rajshahi consistently emerge at moderate levels of concentration, indicating zones of conditional vulnerability where violence intensifies under political pressure.

Recent election cycles and interim periods further demonstrate how these structural vulnerabilities are activated during moments of political uncertainty. Northern districts such as Rangpur, Dinajpur, Gaibandha, and Lalmonirhat remain especially exposed due to long-standing patterns of post-election retaliation and limited access to effective remedies.

Coastal and south-eastern districts -- including Noakhali, Chandpur, Chittagong, and Cox’s Bazar -- have shown a capacity for rapid escalation, particularly in contexts shaped by rumours, social media amplification, and demographic pressures. The recurring appearance of districts in the Chittagong Hill Tracts and parts of the south-west reflects how unresolved land disputes and politicized identity conflicts continue to intersect with electoral competition during transitional governance.

The Numbers Change, but the Risk Remains

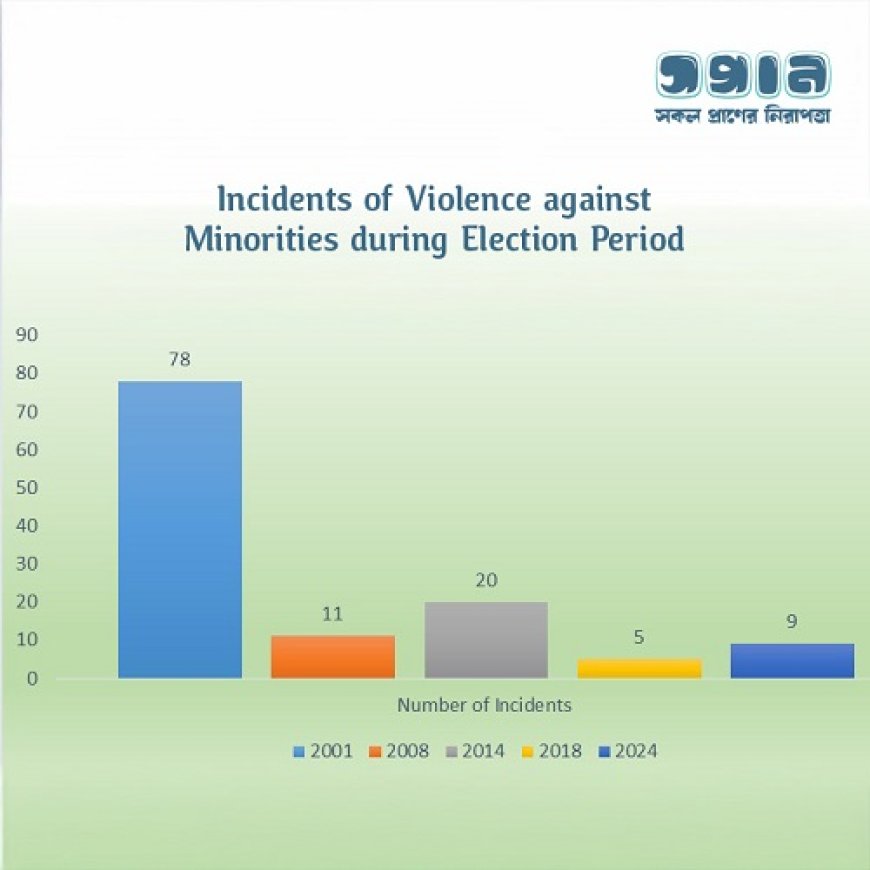

A clear variation is visible in the frequency of reported incidents across election cycles. The highest number was recorded in 2001, with 78 documented cases of violence against minority communities. This figure declined sharply to 11 in 2008, before rising again to 20 in 2014 during a largely uncontested election. In the subsequent one-sided elections of 2018 and 2024, reported incidents decreased to 5 and 9 respectively.

While these fluctuations suggest an overall decline in recorded cases, they do not indicate a corresponding improvement in safety or protection.

Rather, the data point to a shift in the forms and strategies of violence. In later election cycles -- many of which were marked by limited political competition -- incidents became fewer in number but remained diverse in nature, including intimidation, property destruction, displacement, and targeted attacks.

Minority communities have consistently remained politically vulnerable across all periods examined, regardless of changes in electoral participation or competitiveness. This continuity underscores that reduced visibility of violence does not necessarily reflect reduced risk, but often reflects changes in tactics and reporting environments.

As the upcoming election is widely expected to be more participatory, this positive development may also bring renewed political competition and heightened local tensions. In such contexts, historically vulnerable communities are often exposed to increased pressure and intimidation. For this reason, proactive and comprehensive preparation -- grounded in early warning, hotspot monitoring, and community engagement -- is essential to prevent the re-emergence of large-scale violence and to ensure that greater political participation does not come at the cost of minority safety.

Patterns and Forms of Election-Time Violence Against Minority Communities

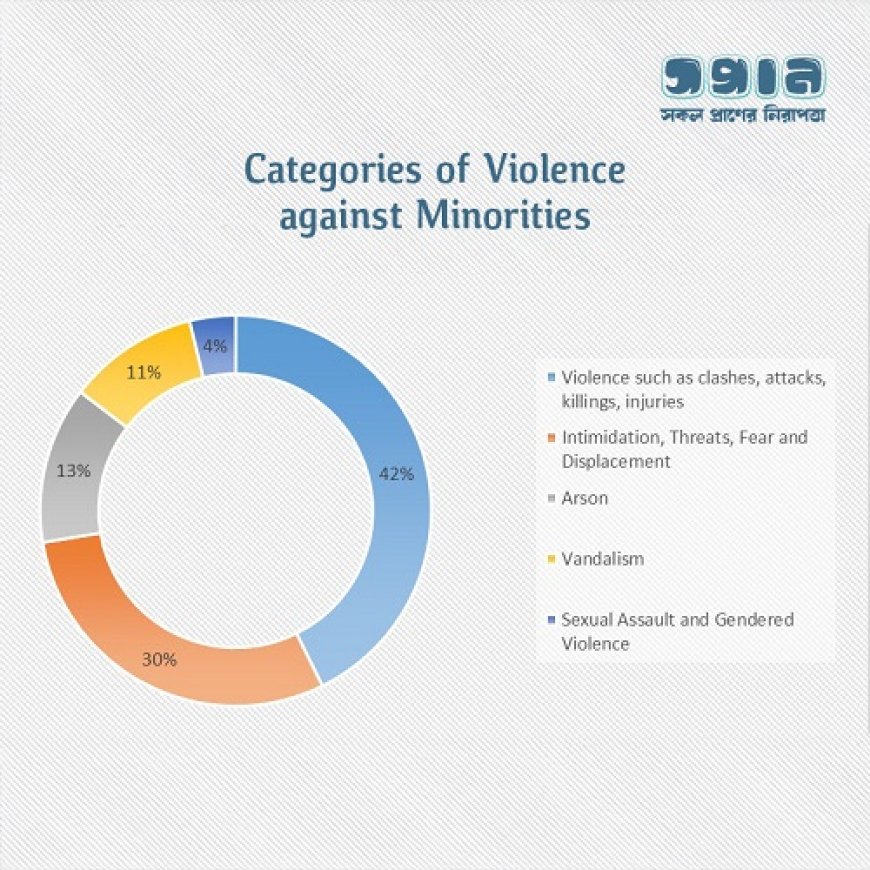

The distribution of violence across categories clearly indicates that coercion, rather than spontaneous disorder, has been at the core of election-time violence against minority communities in Bangladesh. As illustrated in the figure, nearly three-quarters of all documented incidents -- 72.4% -- involved either direct physical violence or intimidation.

This pattern suggests that violence during elections has functioned as a deliberate political instrument aimed at influencing participation, shaping local power relations, and disciplining politically vulnerable communities.

Direct physical violence -- including assaults, clashes, killings, and injuries—accounts for 42.7 per cent of all recorded incidents. These acts represent the most visible and immediate form of coercion, often deployed to send clear signals of dominance and to punish perceived political alignment.

Alongside this, 29.7% of incidents consist of intimidation, threats, fear creation, and forced displacement, highlighting that electoral violence frequently operates through sustained psychological pressure rather than isolated acts of brutality. Such forms of coercion are particularly effective in suppressing voter turnout and inducing long-term withdrawal from political participation, especially among minority communities with limited access to protection or redress.

Property-related violence further reinforces this coercive logic. Arson (13.0%) and vandalism (10.8%) are frequently directed at minority homes, businesses, and religious sites, transforming private and sacred spaces into targets of political repression. These acts not only cause material loss but also signal collective vulnerability, making entire communities feel exposed beyond the immediate electoral moment.

Although sexual and gender-based violence represents a smaller proportion of recorded incidents (3.8%), it constitutes one of the most severe and fear-inducing forms of political repression. Its impact extends far beyond individual victims, producing long-term trauma, social stigma, and deep insecurity within communities. The presence of sexual violence within the electoral violence spectrum underscores the gendered dimensions of coercion and the extent to which elections can become moments of extreme vulnerability for minority women.

Polling Day Is Not the Main Problem

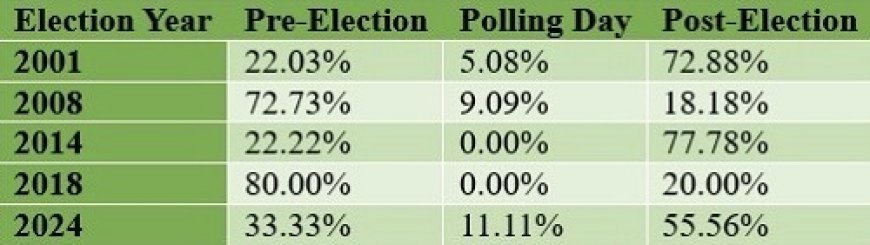

The timing of election-related violence reveals a critical weakness in prevailing security approaches. Contrary to common assumptions, violence has not been concentrated on polling day, and incidents on voting day have remained consistently low across multiple election cycles. In some periods, polling-day violence reached a maximum of only 11.11%, and it fell to zero in both 2014 and 2018. This pattern suggests that heightened security, surveillance, and domestic and international observation on election day have functioned as effective short-term deterrents.

However, these measures have not eliminated violence; they have merely displaced it into periods when institutional monitoring and accountability are weaker. Election-related violence has repeatedly shifted to the pre-election and post-election phases, where coercion can be carried out with greater impunity. In 2001, 2014, and 2024, post-election violence was dominant, indicating that attacks were frequently retaliatory and punitive in nature, aimed at asserting political dominance and intimidating minority communities after electoral outcomes were announced.

By contrast, the predominance of pre-election violence in 2008 and 2018 reflects a strategic use of fear to deter participation and influence electoral behaviour without directly disrupting voting procedures. In these contexts, intimidation, threats, and displacement served as indirect mechanisms of electoral control.

Situation During the Interim Government Period

The ongoing interim period remains deeply concerning, as the vulnerability of minority communities continues to be reinforced by persistent structural weaknesses in protection, accountability, and institutional trust. Transitional political moments have historically exposed minorities not only because of their demographic position, but also because they are frequently perceived as politically aligned or symbolically associated with particular actors.

In such contexts, intimidation, retaliatory violence, and land-related coercion become easier to justify at the local level and more difficult to prevent through institutional mechanisms. The legacy of previous post-election violence further intensifies this vulnerability, as collective memory generates anticipatory fear and lowers the threshold at which rumours, disputes, or minor incidents are interpreted as signs of imminent attack.

While these dynamics are rooted in long-standing historical patterns, the interim period has also revealed important shifts in how violence escalates. Disorder is no longer confined to offline interactions. Social media and digital communication have added a powerful new layer of risk by accelerating the circulation of rumours, recycled footage, and emotionally charged narratives at a pace that often outstrips institutional response capacities.

As a result, localized tensions can rapidly evolve into broader communal threats, frequently before verification, mediation, or preventive interventions can be mobilized. This evolution underscores that contemporary election-related violence is shaped as much by information flows and digital mobilisation as by physical presence on the ground.

The interim period has also produced notable changes in the geography of risk. Several districts that were not consistently classified as high-risk during previous electoral phases have emerged as major hotspots. In particular, Dinajpur, Gaibandha, Lalmonirhat, and Cox’s Bazar have appeared as high-concentration areas, reflecting how weakened oversight and political uncertainty create openings for intimidation, land disputes, and communal targeting.

These emerging patterns indicate that interim governance represents a critical risk window in which historical vulnerabilities are intensified and new fault lines are activated, demanding proactive, coordinated, and phase-sensitive preventive responses.

What Must Be Done

The evidence presented in this study demonstrates that effective protection of minority communities cannot be achieved through reactive force deployment alone. Sustainable prevention must be built through coordinated preventive measures, institutional capacity-building, targeted training, and meaningful community engagement. Security planning must prioritize identified hotspot districts, with particular attention to minority settlements, religious institutions, and community spaces that have historically been vulnerable to attack.

With the election scheduled to take place in the coming days, the need to heighten and strengthen protective measures is now immediate and critical. Preventive security, early warning, and community engagement efforts must be intensified not only on polling day but throughout the pre-election and post-election period, particularly over the next month, when risks of retaliation and intimidation have historically been highest. Authorities must ensure sustained protection of minority communities, their homes, and places of worship during this sensitive window.

Law enforcement and administrative agencies should institutionalise regular dialogue with minority leaders and community representatives in order to strengthen trust and improve early warning capacities. At the same time, online rumours and digitally mobilised intimidation must be treated as serious security risks, requiring systematic monitoring, rapid verification, and timely public communication.

Dedicated emergency response mechanisms should be established and maintained in hotspot districts to ensure swift protection, containment, and support in the event of threats or attacks.

Preventive efforts must also be reinforced through political accountability. Major political parties and candidates should be required to make formal, enforceable commitments to discourage violence and restrain supporters, with clear consequences for non-compliance. Without political responsibility, institutional interventions alone will remain insufficient to disrupt recurring cycles of intimidation and retaliation.

This research underscores that protecting minority communities on the eve of a national election is not merely a human rights obligation. It is a fundamental prerequisite for free, fair, and credible elections. The safety, dignity, and political participation of minorities are central to democratic legitimacy and social cohesion. Failure to ensure their protection undermines public trust and weakens the foundations of democratic governance.

Opshora Islam Tondra is working as a researcher at Sapran.

Md. Zarif Rahman is a member and student representative of the Police Reform Commission and currently serves as the Research Director at Sapran, a right-based think tank.

What's Your Reaction?