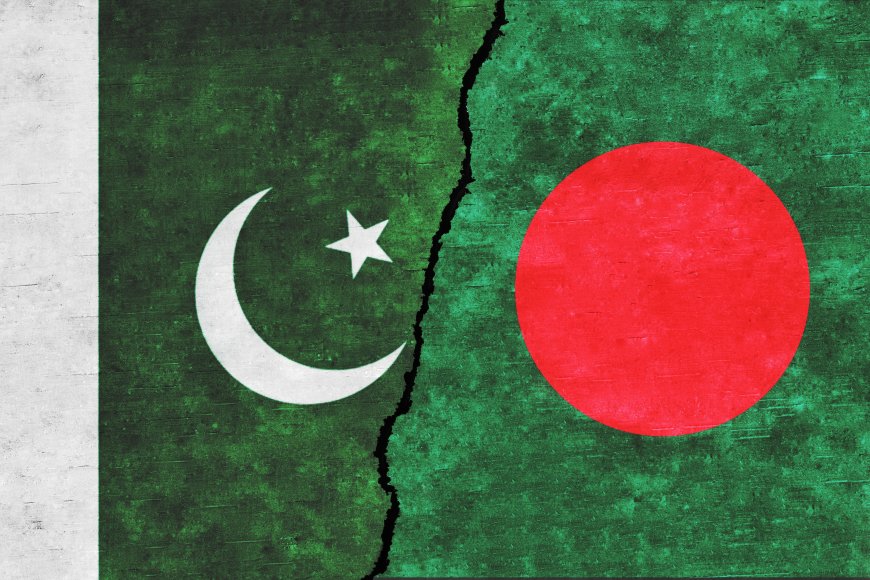

The Burdens of History

Charting a way forward for Bangladesh and Pakistan

Over the past two years, I have spent a great deal of time engaging with the historic events unfolding in Bangladesh. This was a natural outgrowth of my three decades of professional and personal history with Bangladesh and its people, beginning with my first posting in Dhaka in 1990.

I have told these stories enough times that most of my interlocutors understand where I am coming from when I talk about Bangladesh. What fewer people realize is that I also have a deep history with Pakistan, having served three times in that country -- including two tours at the US Embassy in Islamabad and another at the Consulate General in Peshawar.

While I don’t consider myself as much of an expert about Pakistan as I do about Bangladesh, I think this history does provide me with a unique perspective on recent attempts to forge a new relationship between the two countries and their citizens.

The failed attempt to unite the two wings of the erstwhile Pakistan, and the traumatic events of 1971, were topics of many conversations during my tours in Dhaka, Islamabad, and Peshawar. Clearly, the perspective on these events was different, but these conversations were not as cut and dried as one might expect.

In some ways, it was like I was meeting with a couple that had gone through a bitter divorce and who were trying to figure out how to relate to one another in the new reality.

This analogy is not meant to trivialize the suffering of 1971, but rather to highlight the conflicting emotions that I often encountered when talking with my Bangladeshi and Pakistani friends.

Nobody I talked with wanted to turn back the clock and reunite the two countries. But there was a palpable desire to engage in ways that would be mutually beneficial.

The collapse of Sheikh Hasina’s regime in August 2024 and the subsequent efforts to build Bangladesh 2.0 have provided an opportunity for these conversations to move to the next level and for Bangladeshis and Pakistanis (particularly those who came of age post-1971) to construct a new relationship.

For much of the past 20 years, these conversations could simply not take place in Dhaka, as the Awami League regime (and even its immediate predecessor) were loath to provoke a confrontation with India, which was clearly opposed to rapprochement between Bangladesh and Pakistan. The primary regional mechanism for Bangladesh and Pakistani engagement, SAARC, was also hamstrung by Indian hostility.

I often commiserated with my counterparts at the Pakistani and Bangladeshi High Commissions in Islamabad and Dhaka that they were in unenviable positions given the lack of opportunities for real engagement.

With those impediments now removed, there is an opportunity for the Bangladeshi and Pakistani governments and their citizens to chart a new path forward. The first step will be simply to make up for lost time and increase mutual understanding of how each of these countries has changed over the past decades.

In this regard, regular interaction between governments, the private sector, academics, artists, and others can help to counter misinformation and uncover concrete areas for cooperation.

Some encouraging initial steps in this regard have already been taken, including the proposal to build a “knowledge corridor” between Pakistan and Bangladesh. Given the size of these countries and the diversity of their populations, there is scope to expand this interaction exponentially over the coming years.

For Bangladesh, there is a similar opportunity to expand engagement with others in the region and to try to redefine a South Asian community, even as the country looks out to other parts of the world.

Interactions between the respective diaspora communities in third countries can also enrich the dialogue and help uncover areas for future cooperation, particularly for their private sectors.

Of course, the elephant in the room is India, which remains suspicious (if not hostile) to this kind of interaction among the other regional states, and particularly between Pakistan and Bangladesh. The jingoistic Indian media and establishment are quick to embrace conspiracy theories, as witnessed during the most recent Pakistani military delegation’s visit to Dhaka. But while Bangladesh needs to be aware of Indian concerns, the time has long since passed when New Delhi should exercise a veto over Dhaka’s engagement with other countries.

At the same time, Bangladeshis should not engage with Pakistan simply to spite India, but rather because doing so will serve Bangladesh’s interest. It is too soon to determine what specific areas of cooperation will yield the greatest dividends, but it is not soon to begin exploring the possibilities.

From Pakistan’s perspective, there is a great deal to learn from Bangladesh, particularly regarding successful human development strategies. Specifically, Bangladesh’s vibrant non-governmental sector has much to teach Pakistan and the world. There are also natural areas for defense and security cooperation, to include humanitarian assistance and disaster response, global peacekeeping, and regional and maritime security.

While there are plentiful opportunities for bilateral cooperations, closer ties between Bangladesh and Pakistan can also pay dividends in various multilateral forums, where the countries confront shared challenges, including climate change and other transnational threats.

None of the above is meant to imply that Bangladesh should simply substitute Pakistan’s role for that previously played by India, but simply to point out that a healthy bilateral relationship is in both countries’ interests.

The leaders and people of Bangladesh and Pakistan cannot change the past. What they can and should do, however, is shape the future of their own countries and their shared region.

What's Your Reaction?