Subaltern Women and the Islamic Feminist Turn

It's time to rethink the representation and rights of women in Bangladesh. Should elite secular feminism neglect to recognize and engage with Islamic feminist frameworks, it risks irrelevance or worse.

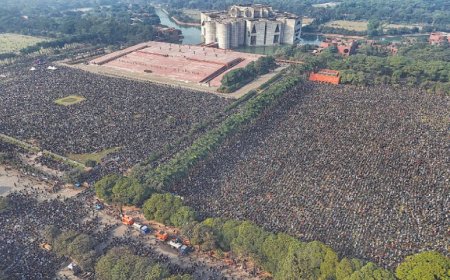

The marginalization of grassroots women's experiences and the absence of their authentic representation amidst urban-centric, elite-dominated, donor-influenced feminist groups have become especially evident following the events of the July Revolution in 2024.

This trend was further solidified by the political rise of Islamic groups within the top educational institutions across the nation. A pressing question emerges: why are Bangladeshi women increasingly opting to affiliate themselves with Islamic groups and their ideologies?

A more subtle inquiry, almost whispered beneath the broader question, is this: if feminist activism in our region has, for many years, been the domain of the educated elite -- those sophisticated, often donor-supported advocates of gender justice -- why are the very grassroots women, for whom such activism was ostensibly championed, now withdrawing from these spaces and instead adopting alternative Islamic frameworks to voice their aspirations, assert their rights, and envision their agency?

To begin to unravel this mystery, one must comprehend the dynamic elements of the feminist subaltern subject in a Muslim majority country, which provides a relational perspective through which to interpret their changing allegiances.

For Bangladesh, a nation shaped by the dynamics of history -- emerging from the colonial oppression of British India, enduring the brutal oppressions of Pakistani governance, declaring a secular ethos at independence followed by the military regimes and the fluctuations of a fragile democracy -- this ongoing cycle of political disruption and reinvention creates the historical backdrop for distinctive identities and cultural terrain against which the subaltern Muslim woman navigates her agency, and, increasingly, her divergence from elite-defined feminist narratives.

Subalternity is not solely established through explicit oppression; rather, it emerges from mechanisms of exclusion, epistemic erasure, economic and social class hierarchies, and the monopolization of representation by prevailing groups -- be they secular elites or international donors.

In these circumstances, women who lack genuine representation frequently discover resonance and agency within religious frameworks, despite the fact that such affiliations may entail enduring contradictions regarding women’s rights.

This shift towards alternative expressions under the framework of political Islam is not an abrupt occurrence; instead, it signifies a persistent trend in which Muslim women in South Asia have navigated agency amidst the limitations imposed by dominant capitalist social, political, and religious structures.

Historically, Muslim women in South Asia have not been the silent figures that colonial narratives or patriarchal ideologies have portrayed them to be. Instead, they have consistently asserted their presence, often balancing modernity and religiosity.

During the colonial period in British India, their involvement in education and writing represented a subversive act, a quiet yet powerful revolution that challenged both the patriarchal defenders of tradition and the imperial overseers of knowledge. The intellectual contributions of Muslim women -- whether through Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s groundbreaking work, Sultana’s Dream, or the establishment of schools that opposed the conventions of female seclusion within the patriarchal frameworks -- illustrated an early insistence that Islam could serve as a resource for women’s liberation rather than a hindrance.

Figures like Sharifa Hamid Ali and Begum Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah embodied this path, utilizing both modernist perspectives and Islamic principles to fight against child marriage, advocate for education, and envision social reforms that would not alienate them from their religious identity.

Despite the fact that, as in many Muslim societies, these pioneering women often came from affluent social classes, this did not confine their activism to elite circles. Their voices resonated widely, reaching grassroots women, and they were accepted, revered, and listened to across social divide.

During the Pakistan period, feminist struggles against the inequalities of Muslim personal law gained momentum, with women’s groups boldly demanding reforms. Their struggle reflected a remarkably advanced and incisive vision of gender equality under Islam for their time, challenging both patriarchal norms and state reluctance. Their activism was animated by a deeper conviction -- that within the sacred texts and spiritual heritage of Islam in this region.

In post-independence Bangladesh, the tension between a formally secular government and the enduring influence of Islamic principles in personal law was captured by the women rights group to pursue their claims.

For many years, women’s rights advocates did not completely dismiss religion. However, by the late 1970s and into the 1980s, the limitations of this compromise became increasingly evident. Feminist organizations started to openly challenge the disjointed system of personal laws that regulated marriage, divorce, custody, and inheritance.

This challenge was swiftly labeled as 'anti-Islamic' by conservative factions, who framed the issue as a conflict between secular feminism and religious orthodoxy. Nevertheless, this was more a matter of political performance than an actual reflection of reality and the aspirations of feminist organizations.

The first calls for a Uniform Family Code arose in this context, echoing debates in India and Pakistan, and became sharper in the 1980s and 1990s under the Islamization drives of military administrations led by Lieutenant General Ziaur Rahman and H.M. Ershad. Unlike pursuing an ideal scenario where feminist engagement with religion could take the form of dialogue and contestation with religious authority, feminist groups expressed insufficient willingness to cultivate progressive Islamic hermeneutics.

The secular orientation of civil society, coupled with the reluctance of male religious scholars, foreclosed such openings. Urban, elite, donor-driven feminism -- dominant in Bangladesh’s women’s movement -- created its own distance from working-class, semi-urban and rural women.

The priorities and idioms of elite activists rarely spoke to women in villages, slums, or semi-urban settlements, who lived with far more immediate struggles around survival. For them, Islamic frameworks provided something secular feminism could not: cultural familiarity and legitimacy in their own communities, and spaces where they could begin to articulate grievances without alienation.

The early 2000s signified a pivotal transformation. Following the global revival of political Islam post-9/11 and the contraction of grassroots NGOs due to diminishing donor reliance and evolving development priorities, women on the periphery increasingly sought out Islamic organizations and groups to advocate for their rights.

Within these environments, through study circles, informal women's collectives, neighborhood madrasas catering to the children of single mothers employed in the garment industry, or emotional and spiritual support networks for women residing in slums, grassroots women uncovered avenues of solidarity and agency that elite organizations frequently neglected to offer.

This shift was not solely religious; it was profoundly influenced by class awareness. Access to education, technology, and mobility heightened grassroots women's consciousness of their marginalization. They began to forge their own paths, searching for frameworks that were socially relevant, locally rooted, and immediately attuned to their lived experiences.

It took decades for the subaltern subjectivity of women to emerge publicly as conscious decisions to pursue rights and agency through Islamic frameworks, a phenomenon that has gained recognition following the July revolution.

The emergence of alternative Islamic spaces for women, particularly following the July revolution, indicates the rise of a distinctly subaltern feminist subjectivity in Bangladesh. This development serves as a reminder that feminism in South Asia has consistently been diverse, fragmented, and contested -- more a series of negotiations among class, culture, religion, and history than a singular entity.

This phenomenon necessitates the incorporation of Islamic feminism, which advocates for the potential of hermeneutic interpretations of the Qur’an and Hadith to promote women’s equality.

In contrast to the orthodox Taliban regime, Modern Islamic feminism envisions women’s liberation as attainable within a religious framework -- a possibility that has been realized, to varying extents, in several moderate Muslim-majority nations.

The robust emergence of grassroots Islamic feminist agency in Bangladesh underscores the importance of acknowledging class, locality, and cultural resonance in feminist practice. Disregarding this trajectory risks perpetuating exclusion, while engaging with it opens avenues for inclusive feminist strategies that respect both agency and social context, ensuring that the voices of subaltern women influence the future of gender justice.

Should secular feminist groups neglect to recognize and engage with the significance of Islamic feminist frameworks, they risk being marginalized by the political strategies of hardcore orthodox Islamic groups, similar to the experiences of feminists during the Shah-era regime in Iran -- where elite feminists, disconnected from the cultural and social realities of the majority, found their emancipatory aspirations abruptly silenced by the rise of an Islamic order that they had failed to foresee, let alone engage.

Dr. Sharin Shajahan is currently pursuing her Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the School of Interwoven Arts and Sciences, KREA University, India.

What's Your Reaction?