The Perils of a Government in an Ivory Tower

Call the vote. Step down from the balcony. And let an elected government answer, at last, to the only sovereign that matters. The antidote to our present malaise is not another announcement. It is an election.

The promise of Bangladesh’s “interim” dawn was intoxicating. On August 5, 2024, the autocrat fell and the heavy sky seemed to crack open. Three days later -- on August 8 -- the chief adviser took the oath. In the breath between those dates, the country lived in a hush: ministries unsure, files unmoving, and the revolutionary crowds learning -- always the hard way -- that victory on the street is not the same as the prose of governance. The calendar itself testified to the vacuum: a nation turning the page without a hand yet to write the next line.

What came after has been a study in hauteur without homework. For months I gave the interim its single laurel: that it had, despite the noise and egos, midwifed a broad Charter of July reforms. That faith is now revoked. The consensus commission’s “enactment” proposals are a Janus-faced betrayal -- an abrogation of the spirit and understandings that animated the Charter in the first place. They narrowed what had been pledged, smuggled in new caveats, and retooled a covenant into a control document. This was not a good-faith translation from street to statute; it was a sleight of hand. Consensus, it turns out, was an instrument, not an ethic -- the applause line that bought time for a rewrite backstage.

The cracks were always visible. Invitations went out unevenly: registered parties were left at the threshold while shape-shifting outfits were ushered in as if proximity could stand in for legitimacy. The choreography pleased the camera; the composition insulted memory. One youth-led party refused to sign on ceremony alone and was mocked for its scruples; in hindsight, its refusal looks like the only grown-up in the room. Consensus by invitation is not consensus by conviction, and today we live with the bill.

Neutrality -- the sacrament of any caretaker -- was the other broken vessel. A caretaker is entrusted to be an umpire, not a captain. Yet we watched advisers slip through revolving doors into party tents and back again; we saw a made-to-measure political vehicle cosseted under the umbrella of state. Worse, official rhetoric often bracketed wildly unequal formations as if history, weight, and sacrifice were irrelevant -- equating the country’s largest, most bruised opposition with a convenience party and a sectarian tail long indicted by memory. Dialogue with all is prudent; pretending that every actor has earned the same moral standing is not. Neutrality that cannot tell the difference between history and opportunism is discretion dressed as virtue.

On corruption, the expectation was not high -- it was absolute. The last order drowned in graft; the interim was summoned to cauterize it. Instead, the public has been fed the old broth -- allegations of access-selling, the rumor of price tags on postings, the petty satrapy of aides who mistake proximity for license. Some of this may be amplified by enemies; all of it rhymes too perfectly with what brought the previous regime down. Clean hands must be more than an argument; they must be a habit the citizen can see.

Worse than policy drift is estrangement from the two guardrails that steadied the transition: the army and the courts. Early on, the military’s tone was one of reassurance -- a defined path to elections, a clear horizon. Months later, coolness replaced cadence: murmurs over timelines and mandates, denials wrapped around visible distance. The judiciary’s arc has been similarly uneasy -- turnover at the top, hurried tinkering with how judges are chosen, and a bench now asserting itself with show-cause orders and flinty speeches about “sustainable implementation.” The choreography may be constitutional; the chemistry is not. States fail not when institutions argue, but when they stop speaking. Ours are speaking -- through clenched teeth.

Service delivery -- where citizens actually meet the state -- has fared no better. Power cuts arrive like old acquaintances; drains turn intersections into brown lakes; schools wait for repairs no one signs; clinics count cotton swabs and run out. Health and education were elevated to commissions and then left to die by committee. Women who helped lead a revolution were asked to applaud from the gallery while men debated quotas and reservations. Patriarchy survived the uprising with its tie perfectly knotted.

The economy wears the verdict in unambiguous ink. We were treated to investment carnivals -- summits with lanyards, panel platitudes, and glossy decks passed like temple offerings. Headlines promised “hundreds of foreign investors.” Then, quiet. No serious pipeline, no meaningful consortium of domestic businesses inside the tent, and almost no attention from beyond our own press. Even the quarterly numbers told on the pretence: a bump followed by a slump, interest that evaporated on contact with reality. Where money did arrive at scale, it was mostly concessional financing for ports or social protection -- useful, yes, but not the private-capital vote of confidence the roadshows were choreographed to suggest. Pageantry is not policy. A roadshow that cannot name its deals is a billboard beside a stalled highway.

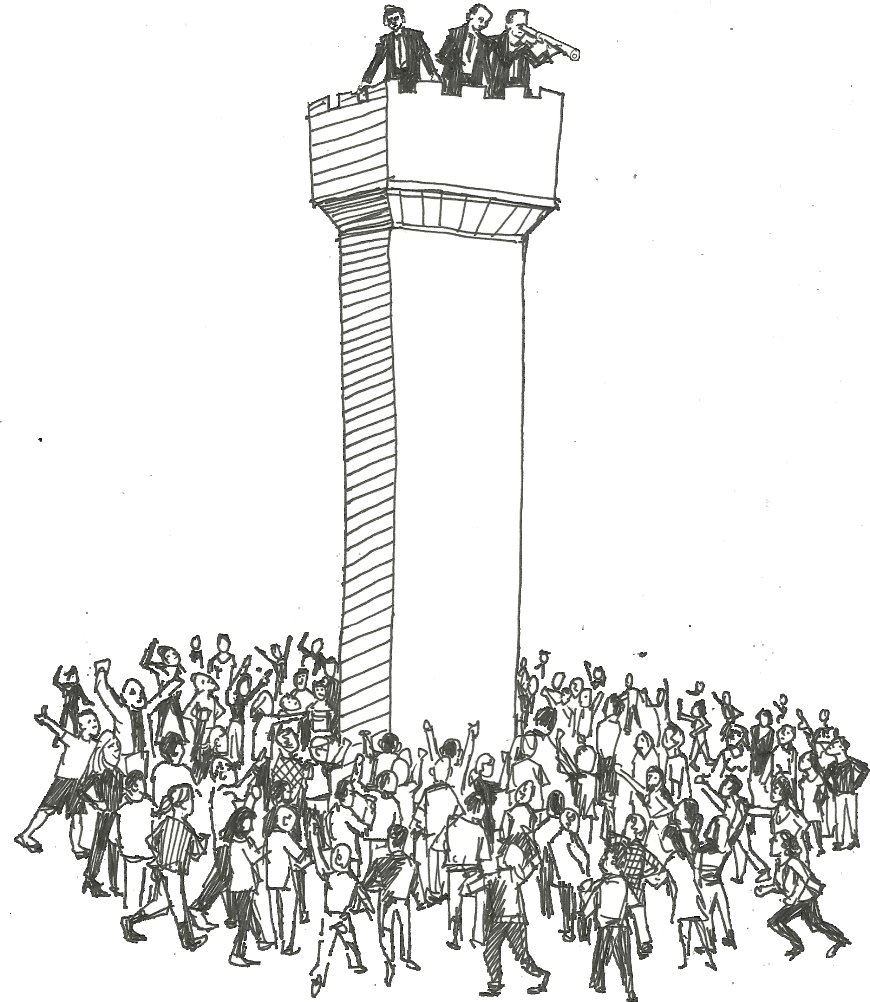

To this theatre the interim added a near-industrial obsession with its own reflection. It built one of the largest public-relations machines any Bangladeshi administration has enjoyed -- press wings to manage the telling rather than the doing, international entourages to proclaim that we had returned to the circuit, the persistent illusion that optics can be banked like foreign exchange. Journalism may breathe with a little more freedom than it did in the dying days of the ancien régime, but trust is not a press release; it is the arithmetic of transparent decisions outnumbering televised addresses. Naipaul warned of rulers who become spectators of their own countries. We are governed, too often, by people peering down from verandas at a public they no longer hear.

Yes, there have been some useful recoveries -- stolen wealth traced, banks probed, past loot documented. But reform cannot be a one-act play about yesterday’s thieves. Citizens asked for re-plumbed institutions, not merely rebranded crusades. They asked for drains fixed creek by creek; for postings insulated from purchase; for procurement rules enforced like scripture; for schools and clinics that function without a press conference. Above all, they asked for the only promise that makes all others possible: a ballot schedule near enough to touch, kept without equivocation.

Arundhati Roy once wrote of states that hover “a little above the law, a little above the people.” Our interim has drifted even higher -- lofty in intention, perfumed by adulation, and yet curiously weightless where the street meets the state. The July Charter was meant to be a bridge; their commission turned it into a trapdoor.

The nation did not break fear to be ruled by mood boards and memoranda, nor to be lectured by an NGO-gram cabinet that mistakes reports for repairs. It broke fear to reclaim the republic.

Call the vote. Step down from the balcony. And let an elected government answer, at last, to the only sovereign that matters. If the metaphor is harsh, the moment justifies it: this interim has behaved less like a steward and more like a parasite, feeding on our dying democracy. The antidote is not another announcement. It is an election.

Bobby Hajjaj is the chairman of the Nationalist Democratic Movement (NDM) and a faculty member at North South University. He can be reached at [email protected].

What's Your Reaction?