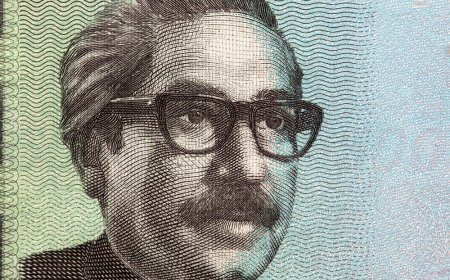

The Disputed Status of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in Post-Uprising Bangladesh

This August 15 , the country must seek closure by coming to terms with the five chapters of its founding President’s legacy –- reckoning with them collectively, not selectively

After the fall of the AL regime, a wide segment of the population not only continued but, in many cases, felt newly reassured in condemning the democratic erosion Bangladesh experienced under Sheikh Hasina’s watch.

Ali Riaz, Vice Chairman of the National Consensus Commission, aptly classified her rule as a textbook case of personalized autocracy: an authoritarian system in which political authority was concentrated in the hands of one leader -- who apparently could do no wrong -- and her family, operating under the facade of a constitution that was cut, stitched, and repurposed to serve the interests of a repressive state, with its core principles selectively applied or ignored.

Policymaking was driven through informal patronage networks, and state institutions -- including the judiciary, civil service, and law enforcement apparatus -- were subordinated primarily to the former Prime Minister’s political survival.

Authoritarianism at its worst manifested through the state-sanctioned killing of at least 1,400 people -- in what plausibly amounts to crimes against humanity, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and several international human rights organizations. Years of pent-up frustration -- fueled by extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances, and financial crimes -- had been sustained by a system that had long made a mockery of the very idea of what a modern state should be.

From a coterie of young activists came full-throated demands to bury the AL -- and with it, its ideology, represented by the one word that has increasingly made the rounds on social media in recent months: Mujibism -- for good.

Those calls have only intensified, as since August 2024, the AL leadership has shown not an ounce of remorse or reflection for its own crimes. That Hasina -- now absconding in India -- is actively conspiring to incite violence should surprise no one.

But as the chants grow in scope and scale, a more complex reckoning looms -- one that has less to do with the deposed Prime Minister herself and more to do with the figure her regime most zealously guarded: Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

During the AL era, Mujib’s portrait loomed over the republic -- adorning government buildings, textbooks, podiums, police press briefings, and nearly everything else. He was both origin story and official doctrine.

In the months following the uprising, the bearing of his name began to shift. Among frontline pro-uprising forces, his name had come to be associated with fascism, dictatorship, systemic looting, impunity, and entrenched criminality.

For perhaps a muted -- but not insignificant -- group who supported the uprising, his contributions to Bangladesh’s founding remain unquestionable and beyond dispute. What binds many is a shared unease about what the future holds for Mujib in post-uprising Bangladesh.

Once a Towering Protagonist, Then an Antagonist, Later a Partisan Football, Eventually a Cult-Like Deity, and Today a Contested Symbol

The story of Mujib can be broken down into five distinct chapters.

First, the pre-1971 Mujib -- the principal political architect of the liberation struggle, whose leadership galvanized a suppressed people under Pakistani military occupation.

Second, the Mujib of 1972 to 1975 -- head of a nascent state tasked with nation-building from ground zero, whose short tenure in government was marked by administrative failures, a repressive tilt, and the eventual concentration of power under BAKSAL.

Third, the posthumous Mujib of 1975 to 1996 -- a period defined by various attempts to marginalize his legacy, as opponents of the AL pivoted toward centre-right nationalism as a counterweight to Mujib’s centre-left politics.

Fourth, Hasina’s Mujib -- whose memory was strategically weaponized, especially from 2009 onward, by a traumatized daughter who invoked him to validate virtually every action -- good or bad -- taken by her government.

Fifth, the Mujib of the present -- characterized by tentativeness.

To acknowledge the second and fourth chapters -- the Mujib who sowed the seeds of one-party rule, and the one whose image was elevated to evoke a later era of authoritarianism -- without affirming the first is to risk being branded, at best, a revisionist or, at worst, an ally of anti-liberation forces, such as Jamaat-e-Islami of 1971.

Yet to affirm the first chapter -- the consequential protagonist that Mujib was -- without confronting the realities of the second and fourth is to appear complicit in the distortions that took place from 2009 to 2024.

The discomfort lies here: in the arc of collective remembrance following his and much of his family’s assassination, it has become nearly impossible to speak of and assess Mujib in totality -- without being accused of betrayal by one side or bad faith by the other.

The fifth and current chapter echoes the third, when Mujib was mostly shelved, leaving unresolved tensions that later resurfaced under the weight of mythologized glorification. Neither the AL nor its opponents -- though to varying degrees -- have allowed time and evidence to be the judge of historical figures.

Each has, in its own way, appointed itself the arbiter of how Mujib -- and other leaders of importance like General Ziaur Rahman -- may be spoken of.

The Hasina regime stands out as the most forceful in codifying such intellectual control -- in Mujib’s case, by constitutionalizing and force-feeding his legacy to the public, without allowing that understanding to develop organically. Doing so nurtured the perception that Hasina fundamentally believed her father alone liberated the country -- and that Bangladesh belonged first and foremost to the Sheikh family.

The AL alienated many who had remained respectful of Mujib -- those who did not support the party but recognized his undeniable place in the country’s formation, while also acknowledging his flaws. What remains difficult -- and necessary -- is to honour the role Mujib played in establishing a sovereign people’s republic without silencing the failures that followed, and to confront those failures without denying the foundation he laid. Cherry-picking aspects of Mujib’s legacy to feed a partisan narrative -- as the AL did -- would be a disservice to the country, and Bangladesh should avoid this at all costs in the coming years.

For Both the Freedom Fighter and the Millennial, Mujib’s Image Became Inseparable from His Daughter’s Personalized Autocracy

Consider one trajectory. A man who had fought in the Liberation War had supported the AL most of his life -- not because he agreed with every political decision that Mujib or his successors made while in government or in opposition, but because he believed no other party better reflected the ideals that gave birth to Bangladesh.

He saw in Mujib the rare convergence of charisma and ideological clarity -- representing secularism and progressive left-of-centre politics. The Six-Point Movement, the Agartala case, and the mass mobilizations of the 1960s made Mujib, in his eyes, the most important Bengali politician of the twentieth century.

But after 2014, and more sharply after 2018, he watched the AL become overtly authoritarian and observed the civil bureaucracy mutate into a self-serving machinery. The AL had abandoned its own pre-Liberation story, even as it continued to govern in Mujib’s name.

Consider another. A millennial -- not born in 1971 but conscious enough to understand what it meant to live through the public safety crises and waves of terrorism that unfolded during the BNP-led period between 2001 and 2006 -- initially found a sense of hope when the AL returned to power in 2009.

The AL pitched a comprehensive vision of Bangladesh that felt different from the past. The trials of war criminals, the launch of Digital Bangladesh, and the laser focus on economic development as a public policy objective -- all of it signaled a party looking ahead. The mega-projects, the early discipline in messaging, and the embrace of an articulate public relations strategy were interpreted as signs of competence.

But starting around 2014 -- and more decisively in 2018 -- the promise of sustainable economic development gave way to heavy-handed authoritarian consolidation. Elections turned into selection processes or formalities. Surveillance expanded across the board. Human rights abuses -- targeting both opponents and many who dared to question the AL, whether on social media or on other platforms -- became too blatant to ignore. The state, no longer distinguishable from the party, ceased to seek legitimacy and began demanding blind reverence. That millennial lost faith in the AL.

At the centre of this increasingly brittle one-party, police-state, mafia-style architecture, stood the portrait of Mujib.

The use of Mujib’s image became more coercive than commemorative under Hasina. It was misused to stifle freedom of expression. By 2024, when the uprising tore through Bangladesh and the regime began to collapse, the rage was aimed squarely at Hasina, her cronies, and the overarching system she had built -- one that wrapped itself in the grandeur and mythos of Mujib, elevating his image to a god-like status and turning installations and state infrastructure into sites of partisan veneration that verged on a cult of personality. Alongside that fury emerged a discomfort with the iconography that had propped it all up.

Anger toward the Sheikh family surfaced when mobs -- directed in large part by certain social media activists based outside Bangladesh -- razed Mujib’s residence on Road 32 in Dhanmondi to the ground. Long preserved as a site of public history, it had borne witness to chapters of Bangladesh’s national life -- both triumphant and tragic.

For the mobs and those who backed them, the attack was justified. Others condemned it. Those approaching it from a rule-of-law lens framed it as an extra-judicial act. The incident was covered by international media -- not in a favourable light. The interim government remained passive. The incident did not resolve the question of where Mujib currently stands in the people’s collective consciousness. It only made the question harder to ignore -- and, simultaneously, more difficult to answer.

The Title Bangabandhu Was Coined by Bengalis in the Late 1960s but Today Many Young People in Bangladesh are Reluctant to Say It Aloud

Even the honorific title Bangabandhu has taken on a far more complicated meaning. It no longer functions as a shared reference point the way it did in 1971. For many, it still carries the moral authority of a leader who personified the dream of emancipation. But for others -- particularly younger citizens -- the word now feels too loaded. To say it aloud is to risk being labelled, instantly and often unfairly, as a partisan -- a dalal of the AL.

After years of being used as a litmus test for loyalty, it is no longer clear whether the term honours a foundational legacy or signals allegiance to an authoritarian regime. That is unfortunate. Today, if someone wants to use the word Bangabandhu to refer to Mujib, they should have every right to. And if someone chooses not to, they should not be compelled to. It is a simple equation.

What Bangladesh is witnessing is a quiet retreat from the word Bangabandhu, even among those who feel a genuine connection to Mujib -- perhaps not out of rejection, but out of caution. The same is true of the slogan Joy Bangla, which once belonged to the people in 1971 but has, over time, become synonymous with the AL -- and is frowned upon by many as a hyper-partisan catchphrase that lost its universal status a while ago. Invoking Joy Bangla today is viewed with skepticism by many who opposed Hasina.

Both of these things are regrettable, and the blame falls mostly on the AL. If Bangladesh is to move forward, it must ask -- and answer -- a series of questions. Will Mujib’s place in the common historical framework be excluded in the post-uprising era? Indications suggest this is already underway -- and to some extent, that retreat was inevitable. But does this trajectory risk opening the door to a new cycle of historical revisionism -- not to glorify, as the AL once did, but to erase, as was the case between 1975 and 1996?

Can the word Bangabandhu be part and parcel of mainstream discourse without inducing suspicion or backlash? Will the horrors of 1971 -- namely Jamaat’s direct role in enabling genocide -- be forgotten because of the outrageous human rights abuses later committed by the AL against Jamaat activists? Is it now acceptable to rationalize the murder of a politician and the killing of his family members? Will it be justifiable to march to and desecrate Mujib’s ancestral home and burial site in Tungipara, Gopalganj?

Most urgently, will any of this lead to the pursuit of truth and reconciliation -- or simply prolong the battle over remembrance? If these questions remain unanswered, Bangladesh risks becoming trapped in yet another generation of unnecessary ideological conflict over the dead -- where history is not studied but weaponized, and energy is drained by endless arguments over who deserves to be remembered, and how. The next elected government will need to step forward and address these questions with conviction.

Because if the country remains mired in unresolved historical narratives, the real work of governing -- the work that actually changes people’s lives for the better -- will remain indefinitely deferred. In the best-case scenario, whether Mujib, Zia, or others, each must be given their rightful place -- without myth-making, without sanctification. That is the path to resolution. That is the path toward closure.

The fact remains: Mujib was an astute politician who, before taking the helm of an independent country, spent over 12 years in prison under British and Pakistani rule -- for the politics he pursued, a politics centered on promoting the inalienable rights of his people.

His politics evolved incrementally: from supporting the Pakistan movement to helping build a party under the guidance of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy -- one that eventually eased out the Muslim League, emerged as the dominant force in East Pakistan, and developed both a strong activist base and a robust organizational structure.

As head of the AL, Mujib secured a decisive electoral mandate in 1970 -- a mandate that was meant to make him Prime Minister of Pakistan. That route -- and that mandate, his oratory skills, along with the Pakistani military junta’s refusal to transfer power to the AL -- cemented his role in the subsequent liberation struggle and raised him to the status of Founding Father of Bangladesh.

A Lasting Political Settlement Demands That the Vacant Ground Once Occupied by the AL Be Reclaimed for Centre-Left and Secular Voters

In Bangladesh, political memory swings between polar extremes. With that, different generations study different histories, but never the full history. If Hasina sanctified Mujib, then with Hasina gone, Mujib must only be condemned -- that is the prevailing mood in many quarters of society.

But such binaries flatten the truth. The story of Bangladesh cannot -- and should not -- be told without Mujib. Nor can the story of a new Bangladesh be written without contending with how he lost popular support so quickly after 1971, how he fell from the heights of revolutionary acclaim to the depths of public disillusionment, and what that arc reveals about the limits of revolutionaries in the complex art of governance.

More than anything, it shows that two decades of fighting the good fight as a people’s champion did not translate into Mujib, the administrator, steering the ship of state in line with public expectations -- due both to his own faults and to geopolitical factors.

It reveals that he was, after all, human -- a flawed politician like any other -- and that even the person in whose name a liberation struggle was waged could become autocratic. He was not someone incapable of making blunders.

On the flip side, his assassination was vicious and condemnable, and must be seen for what it was: an insult to the very humanity Bangladesh liberated itself to uphold. His assassination also laid the groundwork for antagonism between opposing ideologies, enabling people to justify reprehensible actions in the name of politics.

After 2009, his image was not simply remembered -- it was repurposed and repackaged by his daughter as a political tool to give her the bandwidth to reshape the country on her terms. That full story is the truth. Moving forward, Mujib must be taken back from a party that claimed exclusive ownership of his legacy.

Any path forward must create space for voters who now find themselves isolated -- particularly those who supported the AL because they believed in its stated centre-left, secular orientation and its ideological opposition to Islamist-influenced politics.

This bloc traditionally comprised 30 to 40 percent of the electorate, according to data from four relatively credible elections between 1991 and 2008. The number is likely smaller now, but still not negligible. The average AL supporter cannot be perceived as having committed crimes under the law unless they are actually indicted for violating provisions of the Criminal Code or other domestic or international legal doctrines.

Beyond this, if they are to be faulted, it is for moral shortcomings, including but not limited to failing to speak out against the AL’s authoritarianism -- a silence that was deeply lamentable, but that does not, and should not, erase their democratic rights or disqualify them from future political engagement.

The centre-left space is now largely vacant and up for grabs, but no major stakeholder seems willing to occupy it. While the BNP positions itself near the centre, it has always functioned as the anti-AL alternative and, as such, the default anti-AL party to vote for.

That centre-left vacuum comes at a time when Islamist parties appear poised to mount their most visible and vigorous electoral campaign to date. Whether that translates into electoral gains remains to be seen.

At the same time, apprehension is growing among citizens who see efforts -- direct or indirect -- to diminish the centrality of the Liberation War by placing it on par with the 2024 uprising, alongside attempts to redefine Mujib’s place in the country’s fluid landscape.

This tendency is most visible among certain factions aligned with the uprising -- particularly those to the right of centre, including Islamist parties and the NCP.

Citizens’ concern stems from uncertainty over who will control how the country’s past is understood, and whose version will dominate in the years ahead. The Liberation War remains the primary reference point in Bangladesh’s civic life -- unmatched by any popular movement before or since, including the uprisings of 1990 or 2024.

The events of 2024 were historically momentous -- an inflection point for Bangladesh -- and will continue to shape how the country’s history is interpreted. But they do not -- and cannot -- belong to the same category as a war for independence against a foreign entity.

Preserving the Liberation War’s centrality is not about defending historical emblems. Rather, it is about safeguarding the foundation on which future political norms and expectations will be debated and defined.

Bangladesh is a small, densely populated country with finite resources, a dysfunctional state apparatus, high unemployment, and a population that has, writ large, been failed by both political and public policy stakeholders.

It is tired. It is drained. It is, perhaps, a bit too combustible at the moment. And it bears the scars of a societal culture warped by authoritarianism, tit-for-tat vendettas, and a zero-sum mentality in which criminality has been normalized and livelihood often demands substantial moral compromise.

In many, a miniature autocrat has taken root. These are not conditions in which perpetual antagonism can endure. Co-existence is not a choice -- it is an imperative. Justice and accountability are not optional either -- they are indispensable to democratization.

But fixating on the dead will not fix the country. What patriotism now demands is creativity, discipline, the ability to conceptualize and implement sound public policies, and an allegiance to seeing the bigger picture.

The past cannot be undone -- but the future remains unwritten. Let it be authored together by those willing to build Bangladesh, not just break.

Mir Aftabuddin Ahmed is a Canada-based public policy columnist, with over 140 published articles across Bangladeshi and Canadian media platforms and policy publications. He can be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed in this article are his own.

What's Your Reaction?