Delaying the Announcement of an Election Roadmap is No Longer Tenable

Bangladesh now stands at the threshold between gridlock and reconstruction — the Chief Adviser must set a specific month for the upcoming elections and do so without hesitation.

The interim government’s honeymoon period is over. A soft spot had understandably existed, given the shattered state apparatus that Professor Muhammad Yunus inherited nine months ago. The window of a grace period -- extended in practice by all political parties except the deposed Awami League and its allies -- has now closed.

That space, which opened in August 2024, was never meant to be indefinite -- and rightly so. A permanent blank cheque for Professor Yunus to govern without political scrutiny is not realistic in a country like Bangladesh.

It is now clear that the Chief Adviser is perhaps frustrated and increasingly out of his comfort zone -- both in managing the political ecosystem and in dealing with noticeable friction between his government and the armed forces.

But the frustration is mutual: both the armed forces and the country’s largest political party at the moment -- the BNP -- are showing explicit signs of discontent with the interim government.

Political and Institutional Realities Demand a Concrete Election Month

What must now follow is a defined election roadmap. That single move will begin to repair the trust deficits and perception gaps that have emerged in recent months. At this stage, the bare minimum is a solid guarantee by the Chief Adviser of the specific month in which elections will be held.

Doing so would trigger the pre-election constitutional timeline -- requiring that a formal election schedule, including the polling date, be announced no later than three months before the election month. In addition to naming the month, the roadmap should contain three further elements.

First, an assurance that any legal reforms or electoral code amendments will be completed no later than 60 days before the official campaign period.

Second, a mechanism for structured dialogue between the interim government, the Election Commission, and political parties to ensure transparency, consultation, and adherence to the timeline.

Third, a plan to resource and operationalize the Election Commission’s administrative readiness -- including deployment schedules, ballot logistics, and coordination with civil and law enforcement personnel.

Without laying out a tangible roadmap, the government will struggle to do its job in relative comfort, key stakeholders will remain on edge, and speculation and rumors will define the political climate.

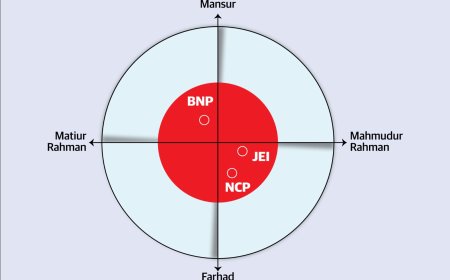

The need for a roadmap intersects with four arenas. The first is politics. Barring the NCP and a few Islamist actors, major stakeholders -- including the BNP and the armed forces -- have advocated for elections by December 2025. Jamaat, while slightly more flexible, has pointed to the pre- or post-Ramadan period as the latest acceptable window, meaning by March 2026.

The NCP, along with smaller Islamist actors, has signalled openness to a more extended timeline, even into June 2026 -- a position aligned with the longer end of the Chief Adviser’s stated range of December 2025 to June 2026.

These varying timelines are sharpening the gap between the interim government’s inner circle -- including the NCP -- and its most powerful interlocutors: the BNP and the armed forces. Jamaat remains tactically noncommittal, wandering between the two opposite positions.

Time for Political Stakeholders to Show Results of a Historic Reform Exercise

The second arena is the reform process. Contrary to prevailing social media discourse, broad consensus has developed behind the scenes among political parties on a significant number of reform proposals -- a fact that has largely gone under the radar, as both mass media and online commentary have focused more on areas of disagreement than on existing common ground.

In recent days, Professor Yunus has met a couple of times with all major political parties following the controversy surrounding his reported intention to resign.

These meetings appear set to continue under the banner of the National Consensus Commission, which will soon launch the next phase of its work: building material agreement among parties on unresolved or contentious issues -- including the composition and formation of future election-time caretaker governments, the process for electing the President, and term limits for the Prime Minister -- by mid-July.

That deadline offers a natural moment to consolidate progress in a written consensus document in the form of a national charter, for which all key players appear to have a genuine appetite.

Reform recommendations with political backing -- that is, where consensus exists -- should be incorporated in the national charter and implemented through Presidential ordinances rapidly. Reforms requiring a sitting parliament must be deferred until after the election, but only after parties provide signed guarantees -- within that same national charter -- to enact them.

Where consensus cannot be reached, proposals should be put to voters. Parties can campaign on those issues and seek a mandate at the ballot box. That is how democracy works.

It is also how Professor Yunus has articulated his historic role -- a facilitator of a complex transition, not a reformer with his own agenda. His word, more than anything, is his bond. Bangladesh expects him to honour it.

A roadmap should be developed with the mid-July milestone in mind -- the point by which Bangladesh is expected to have a clear idea of what the national charter will include -- or, at the very least, be timed to coincide with it. The roadmap could be announced before mid-July or confirmed right after the charter is signed.

Communicating that intention now would stabilize the political climate and sway political actors from protest and escalating demands toward electoral preparation.

At present, most parties are caught between posturing and planning, unsure whether to prepare for elections or brace for further delay. That uncertainty must end immediately. The government should be allowed to complete its work on the basis of a transparent timeline -- something only it can provide -- and an outlined scope of authority, based on agreed-upon reforms.

Professor Yunus Needs to Give the Private Sector a Clear Signal About What Comes Next

The third arena is the economy. By the end of Sheikh Hasina’s final term, Bangladesh’s economic health had severely deteriorated -- and the interim government inherited a fiscal, monetary, and financial mess. A devastated banking sector, institutionalized money laundering, severe liquidity shortages, and stagnant investment patterns created a gravely fragile baseline.

On top of that, the methodical dismantling of constitutional pathways for a democratic transfer of power -- engineered by what, by the end, became a brutal authoritarian Awami League regime, first and foremost because of its refusal to hold credible elections and its decision to unleash mass atrocity crimes on the people of Bangladesh -- left a popular uprising as one of the few remaining correctives.

That, too, came at a cost -- unpredictable in both its depth and duration. The natural fallout of a mass uprising is economic uncertainty and volatility, and that continues to grip every major economic sector, all of which are now struggling to understand what comes next politically.

Investment, both domestic and foreign, is sluggish. Consumer and business confidence remain low -- and for good reason. Investors require political stability and predictability, neither of which is possible without an unambiguously stated path to elections and their timely holding. A government without a defined endpoint -- not the preliminary six-month window Professor Yunus has spoken about -- cannot offer that.

A signal from the top indicating a specific election month would help restore planning horizons and provide the clarity that economic actors have repeatedly asked for. The consortium of entrepreneurs, industry leaders, economists, and chambers of commerce have -- de facto, using different language -- all articulated the same demand: an election roadmap.

They do not expect the economy to rebound by magic. But they do expect the political transition to aim toward an obvious electoral destination. Reform is critical. Placing foundational trust in Professor Yunus is also non-negotiable. But neither can substitute for economic certainty. An election roadmap is the best vehicle that can carry all three -- reform, recovery, and credibility -- in parallel.

The Interim Government Is Mandated to Prove That It Is a Great Unifier

The fourth arena is the interim government’s political mandate. The interim government was appointed through a special provision -- a measure of last resort -- in the constitution: the doctrine of necessity.

Under that doctrine, the Head of State -- the President -- appointed a Chief Adviser and an Advisory Council to serve as the executive branch -- in effect, a Cabinet -- in the absence of a functioning parliament. The ad hoc arrangement has legal standing, supported by a Supreme Court opinion.

But constitutional legality alone is not enough. The interim government’s authority also rests on a wider base of legitimacy -- one shaped by three forces.

First, the mainstream parties that opposed the Hasina regime. Second, the armed forces, which filled the vacuum between Hasina’s departure and Professor Yunus’ appointment and continue to provide domestic security in a role that extends beyond their traditional mandate. Third, student actors now largely organized under the NCP.

Leaning toward the NCP without giving due weight to the BNP and the armed forces -- both of whom hold far more pull writ large -- would be a serious political miscalculation.

Other than announcing the election roadmap, the interim government should focus its collective energy on several political and policy items of national importance.

First, the Chief Adviser must step into a more visible leadership role. That means reducing international travel, increasing domestic media engagement, continuing to chair the upcoming National Consensus Commission meetings with political parties, and maintaining steady, direct communication with the armed forces to prevent misalignment -- even if that communication remains off the record.

Second, on sovereignty-related matters -- including the future of Chittagong Port and the Rohingya corridor -- the interim government should not make binding decisions. But it can begin consultations, lay the groundwork, and ensure the road is clear for the next elected parliament to decide on these issues.

Third, Professor Yunus must distinguish between what can be implemented now, what must wait until after the elections, and what belongs in the hands of voters at the ballot box.

An endless reform exercise with no clear end date -- particularly if framed as an alternative to announcing an election roadmap -- will lose support. Elections held without reforms based on good-faith consensus will sideline the aspirations of the Bangladeshi people. A roadmap, rooted in the realities Bangladesh now faces and tied to a specific month as a starting point, is the optimal path forward toward stability.

Whether it is the pace of processes related to trials for crimes committed under the Awami League regime during July and August 2024, or the scope and scale of reform efforts -- both of which are already underway and should be accelerated -- neither should substitute for, or contradict, a crystal-clear announcement of when elections will take place.

Calling for elections is not a detour from reform -- it is what turns reform into reality. Oxford economist Paul Collier argues that it takes three to four electoral cycles for democracies to consolidate. Only through the rinse and repeat of credible elections do political actors internalize the rules of the game, and state institutions begin to function as intended.

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, in their work on political development, demonstrate that reforms cannot endure without political legitimacy -- and legitimacy depends on the consent of the governed. Regular, inclusive elections are what give reforms their staying power.

Without electoral validation, even the most well-intentioned reforms risk being reversed or rejected. After a lost decade of rigged and non-competitive polls, hosting a free, fair, and competitive election is not just a democratic reset -- it is a frontline component of the reform package Bangladesh urgently needs.

Those who dismiss that demand as reckless are missing the point. Reform lays the foundation -- but only elections can test it, entrench it, and make it last. One without the other cannot stand.

To repeat: the grace period has incontrovertibly ended. The window to act thoughtfully -- and with the buy-in of all, not just some, of the stakeholders who have a stake in the future of Bangladesh -- remains open, but certainly not for long.

The interim government has the opportunity to rise above the divisions now being manufactured by various players -- including some within or associated with the government itself -- and become the thread that weaves this fractured nation into a shared future.

The people of Bangladesh have endured too much, waited too long, and paid too high a price -- including the loss of over 1,400, mostly young, lives during the mass uprising -- to settle for anything less.

Bottom line: Professor Yunus must be the great unifier. Otherwise, Bangladesh will tear itself apart from within. History is watching. There is no path forward but together.

Mir Aftabuddin Ahmed is a Canada-based public policy columnist, with over 140 published articles across Bangladeshi and Canadian media platforms and policy publications. He works as a Policy Development Officer with the City of Toronto and can be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed in this article are his own.

What's Your Reaction?