I have got a job, but …

Unlocking opportunity by tackling Bangladesh’s employment challenges

One of the critical issues confronting Bangladesh is the challenge of generating productive and remunerative jobs for millions. The challenge is both long term and urgent. It is long term because many years of sustained effort will be required to meet the challenge. But it is also urgent because any delay in taking necessary actions will make the problem much harder to solve.

Aspirations and frustrations

Bangladesh’s fast-growing economy has generated aspirations. Rising aspirations suggest that more and more young people would want a university education. Rising incomes mean that many families can now finance such ambitions.

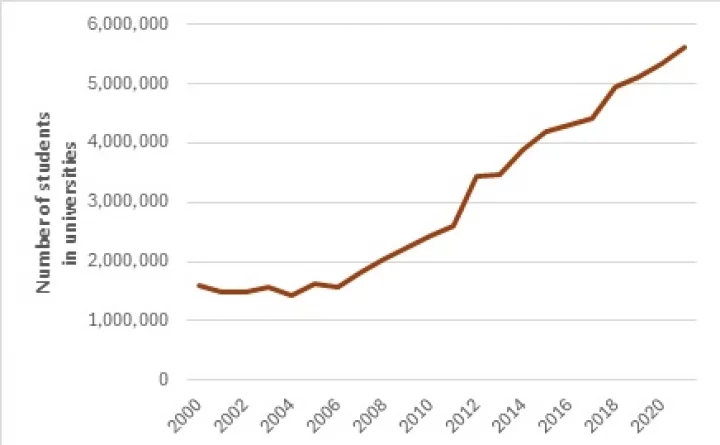

It is thus no surprise that there has been an explosive growth in university education in recent years. Figure 1 shows the trends in graduate enrollment (ie, number of students in universities and graduate level colleges) for the period 2000-2021 (the data are from various issues of the Bangladesh Economic Survey, an annual publication of the Ministry of Finance).

Figure 1: Number of graduate students: 2000-2021

After remaining fairly stable at about 1.5 million in the first six years of the new century, graduate enrollment started expanding rapidly from 2007. By 2021, it was 5.6 million -- 3.5 times the level in 2000.

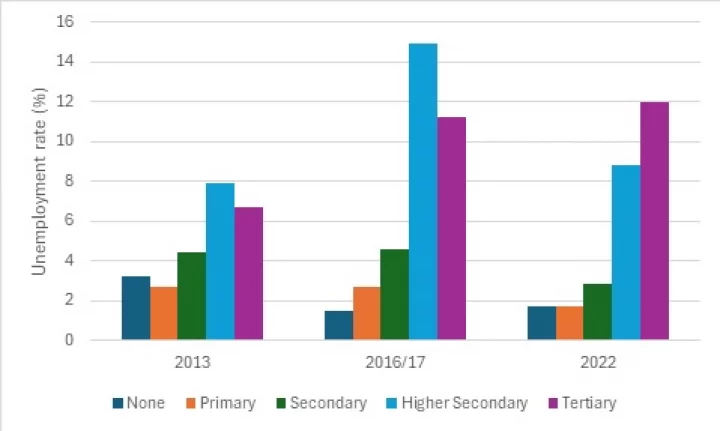

This phenomenal rise in graduate enrollment has not been matched by job creation. This is starkly brought out in the second figure which shows recent trends in unemployment rates by education levels (the data are from the periodic Labour Force Surveys carried out by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics). As we can see the unemployment rate for those who have received tertiary education has almost doubled in the last decade (from 6.7% in 2013 to 12% in 2022).

Figure 2: Unemployment rates by education levels 2013-2022

That is about youth unemployment. What about the rest of society?

Let us take a hard look at the issue using data. The best source of employment related data is the Labour Force Surveys (LFSs) carried out by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Across the globe, surveys such as these are used by statistical agencies to assess employment related patterns and trends. In Bangladesh, the LFS is carried out at an interval of 3-4 years. The latest survey was carried out in 2022.

Let us start with two important variables, the working age population and the labour force participation rate. The working age population is defined as everyone aged 15 and above. A more restrictive definition would include people between the ages of 15 and 64. In this note we use the broader definition. The labour force is a subset of the working age population. It consists of those who are employed and those who are unemployed, ie, not employed but looking for work.

Those of working age but neither employed nor looking for work are not considered part of the labour force. People of working age do not enter the labour force for various reasons. For instance, many women may opt to spend their time doing household work instead of working outside the home. The decision may be voluntary or imposed by circumstances, family pressure, or social norms. Sometimes, people frustrated with their job search efforts decide to withdraw from the labour force. Also, many people of working age are students and don’t enter the labour force till they finish their studies.

For these reasons, it is expected that a small subset of working age people would not be in the labour force. If a large proportion of the working age population is not in the labour force, it could mean a serious underutilization of human resources. Thus, the labour force participation rate, ie, the proportion of the working age population in the labour force, is an important variable.

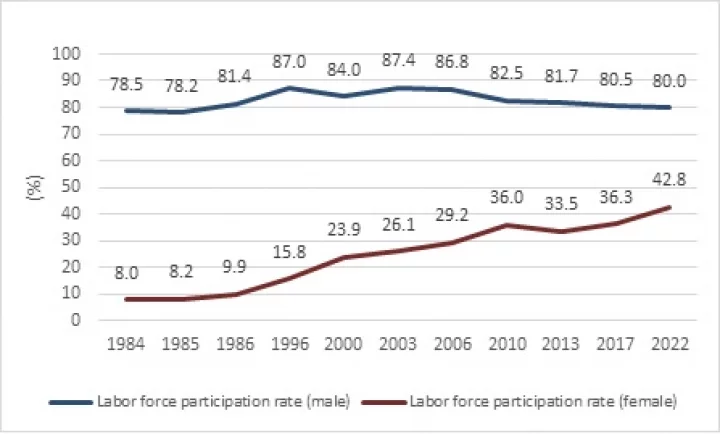

The women are coming out

The labour force participation rate (LFPR) for men has been high for the past four decades, fluctuating between 78 and 87%, with an inverted U-shaped long-term trend (Figure 3). The male LFPR increased from about 79% in 1984 to 87% in 2003 but then dropped to reach 80% in 2022. In other words, the gain in the LFPR for men during the first half of this 40-year period was mostly wiped out in the second half.

By contrast, the female LFPR shows a steadily increasing trend over the past four decades. Women did not participate much in the labour force in the 1980s, when their LFPR ranged between 8 and 10%. But then the situation changed. Barring a slight dip in 2013, the female LFPR has steadily increased in the last three decades to reach almost 43% in 2022. More and more women are now joining the labour force. Although there is still a huge gap between the male and female LFPRs, it is narrowing.

Figure 3: Labour force participation rate: 1984-2022

These are national trends. Is there a rural-urban difference?

I have data only for recent years. In 2010, 2013, and 2016/17, there was no significant rural-urban difference in the LFPR. However, in 2022, the urban LFPR decreased to 51% from 57% in 2016/17, while the rural LFPR increased from 59 to 65% over the same period.

Most people are doing something, but …

According to ILO definition, which is followed for the Bangladesh LFS, unemployed persons are defined as all those of working age who did not work for a single day during a specified period (for the Bangladesh surveys, the reference period is the seven days preceding the survey) but were trying to get a job and are ready to work if given a job. In other words, these are people who wanted to work but did not find any work.

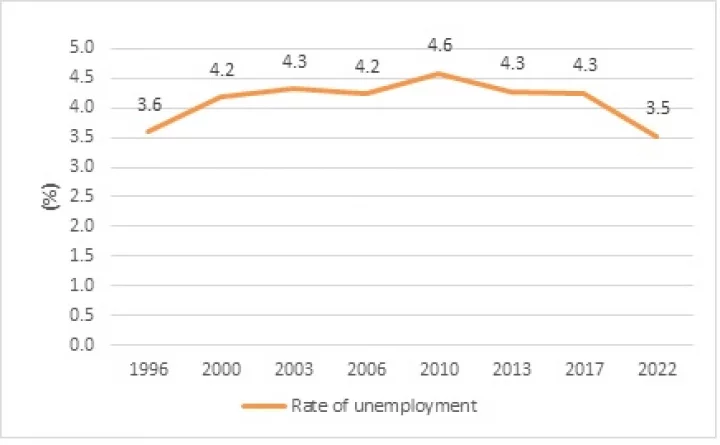

The long-term trends in the unemployment rate (1996-2022) are shown in Figure 4. The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the total labour force. We may note two important things. First, the long-term trend shows an inverted U-shaped pattern -- the unemployment rate steadily jumped during 1996-2010, rising from 3.6% to 4.6%, but then fell and, by 2022, reached 3.5% (roughly level in 1996). Second, the overall level of unemployment -- ranging between 3.5 and 4.6% -- is actually not that high by global or developing country standards.

Figure 4: Rate of unemployment: 1996-2022

… but the jobs are not of good quality

There is a catch here. And this has to do with the quality of jobs. People may have a job but it may not be of good quality. There are many aspects of employment quality, and I shall highlight just one, the proportion of informally employed people.

Informal employment is usually less remunerative. According to the Bangladesh Labour Force Survey 2022, informal employment refers to the total number of informal jobs, whether carried out in formal sector enterprises, informal sector enterprises, or households (paid domestic workers, goods production for own consumption), during a given reference period, which is the week preceding the survey. Informal sector enterprises are typically owned by individuals or households that are not constituted as separate legal entities independently of their owners.

Such enterprises are not registered with the government and typically have a small number of employees. In the Bangladesh LFS, household enterprises with less than five paid employees are considered part of the informal sector, provided they are not registered. Employees of informal enterprises generally lack basic social or legal protection or employment benefits.

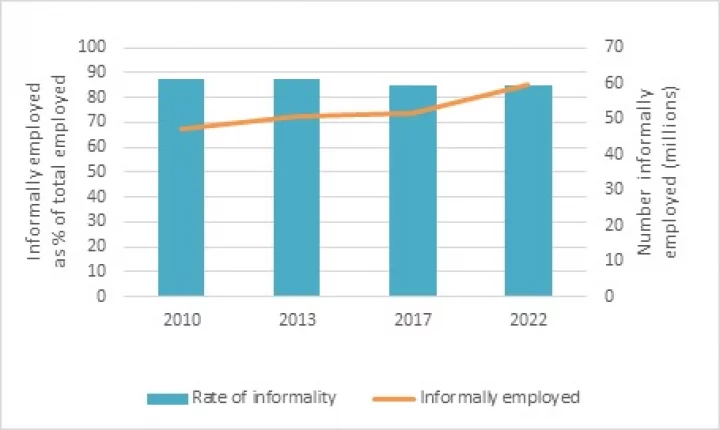

As we can see from Figure 5, about 85% of jobs are informal in nature. The rate of informality has gone down over the past decade and a half, but very modestly. The 84.9% rate in 2022 is not much different from the 87.5% in 2010.

The implication is clear. For the vast majority of Bangladesh’s employed, the employment conditions are unsatisfactory. The jobs are insecure, earnings are poor, productivity is low, and the working conditions are nothing to write home about.

Since the number of employed people have been going up over the years, the consistently high degree of informality means that the number of people working in poor conditions with low earnings has been increasing as seen by the straight line. In 2022, almost 60 million people were working in the informal sector, up from 50 million in 2010.

Figure 5: Informal employment: number and rate: 2010-2022

India’s renowned labour economist Ajit Kumar Ghosh, who passed away last year, published a short but very informative book on employment trends in India in 2019, called simply “Employment in India.” In that book, he wrote: “Employment constitutes the critical link between wealth and welfare, between economic growth and improvement in the level of living of the population in a country. This is why development strategies cannot just be growth strategies; they must be ‘growth with employment’ strategies.”

That comment is not necessarily saying anything new, although in our fascination with growth we often forget the importance of creating jobs. But, in that book, Ghosh also reminded us that mere jobs are not enough. The quality of jobs matters too.

What's Your Reaction?