Lessons from Kathmandu: Why Bangladesh’s Next Government Faces an Existential Test

What can those who hope to rule Bangladesh post-elections learn from recent events in Nepal, and what are the twin threats that it will need to face down?

In recent times, we have seen uprisings first in Sri Lanka, then in Bangladesh, and most recently in Nepal.

In all three cases, political violence was prominent. Centers of power, as well as the properties and residences of political leaders, came under attack. These uprisings, driven by mass movements, were carried out by ordinary people.

The central causes of public anger were corruption, repression, and abuse of power. Students and young people played a leading role in Bangladesh and Nepal, while in Sri Lanka the younger generation became the face of the movement.

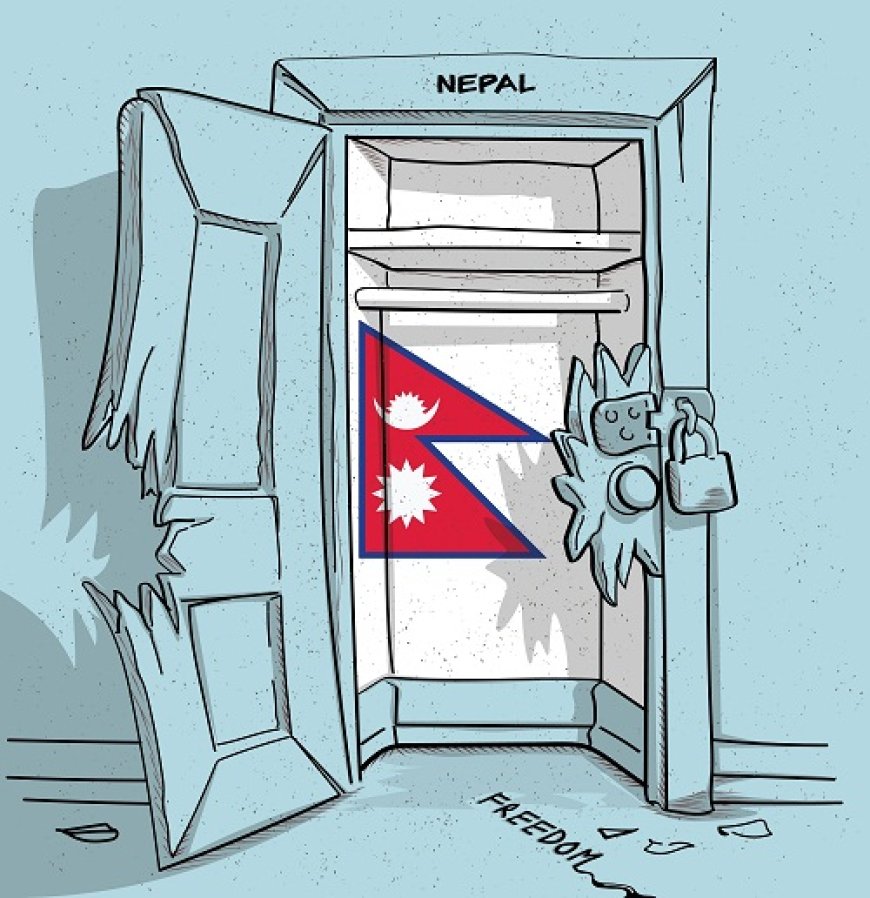

Nepal’s experience is particularly noteworthy. The country had a democratically elected parliament, and the government came to power through elections and referendums. At the center of the movement in Nepal was corruption. During the uprising, both the government and the opposition came under attack from the people.

In other words, it was not simply a regime change but an expression of distrust toward the entire political class. In political science, this is called anti-establishment mobilization. Here we can apply Lipset’s legitimacy theory: when a state loses public trust due to corruption and incompetence, even a democratically elected government cannot sustain its legitimacy.

From this, Bangladesh’s next government has important lessons to learn.

The August 5 uprising in Bangladesh was not the end. This may sound uncomfortable, but let us think rationally rather than emotionally.

After August 5, two possibilities have emerged. In the changed context, the BNP hopes to win the next election and form a government.

On the other hand, the Awami League, one of Bangladesh’s major parties, is currently out of politics. Yet this party is gradually reorganizing. If the normal legal process does not allow the Awami League to return to politics, then sooner or later it will attempt to re-enter through another event like August 5 -- this cannot be denied. Only the timing is uncertain.

Samuel Huntington’s Political Order in Changing Societies helps us understand this: organized political parties cannot be excluded from politics for long. If their path back is blocked, the risk of future violent explosions only increases.

Beyond the Awami League question, another power center has emerged. This center is led by religion-based political parties. These include parties aligned with the Maududian tradition as well as more radical factions that embrace Islamist ideologies like al-Qaeda or Hizb ut-Tahrir.

Among them, the most organized and powerful is Jamaat-e-Islami. In terms of organization, finance, political base, and intellectual capacity, Jamaat is ahead of the rest -- there is no doubt about that. While at this moment they are not in a position to take national power, within the next few years their influence could grow exponentially. With that growth comes the question of whether this Islamist bloc will respect democratic politics or, following Charles Tilly’s concept of contentious politics, take a revolutionary path. If they choose a Nepal-style revolutionary path, it would not be surprising.

For now, it can be said that BNP’s opponents have succeeded in embedding the perception that BNP is a corrupt party in the public mind. According to labeling theory, once a label of corruption is attached to an organization -- whether true or false -- it shapes social reality. If BNP comes to power, this perception could intensify, since Bangladesh’s state structure is weak in controlling corruption.

In this context, the next government will face two existential crises:

1.The relentless attempt by the Awami League to return to politics, likely with the help of neighbors, and the violence associated with that attempt. As Samuel Huntington once warned, organized political actors cannot be permanently locked out of politics. If normal, legal avenues remain closed, they will eventually try to break back in -- and the result is rarely peaceful.

2. The growing pressure from the Islamist bloc and their project of establishing an Islamic state is another challenge. Here, the concept of the radical flank effect is critical. Scholar Herbert Haines coined the term to describe how the rise of more extreme voices can drag moderates in the same direction. What was once considered extreme -- an Islamic state project -- gradually becomes normalized. This is the real danger. Moderates bend, the center shifts, and radical ideas begin to look less radical. Over time, this could push Bangladesh into a cycle where religion dominates politics in ways the country has not seen before.

Under these two pressures, the survival of a weak government will be extremely difficult. Therefore, there is no guarantee that another event like Nepal’s will not occur in Bangladesh. The real question is whether BNP is genuinely prepared to reduce this risk -- or whether they assume that simply forming a government under “normal circumstances” will be enough.

The reality is, Bangladesh is no longer in any “normal time.” We are at a turning point in power politics where even the very character of the state is in question. The issue now is whether those who want to pursue liberal democratic politics are prepared for governance in this new reality, or whether this conflict will once again push the country toward military rule.

Asif Bin Ali is a Doctoral Fellow at Georgia State University. He is the co-editor of the book The Emergence of Bangladesh (Palgrave Macmillan). Email: [email protected].

What's Your Reaction?