Bangladesh Has Passed the Electoral Test, But Can It Keep the Republic?

Bangladesh has held many elections since independence in 1971. But few have carried the weight of this week’s vote. Now comes the harder test: Proving that victory does not mean domination.

Bangladesh has held many elections since independence in 1971. But few have carried the weight of this week’s vote. This was not simply a contest between parties. It was a referendum on the post-uprising order that emerged from last year’s Monsoon Revolution, the youth-driven movement that toppled one of South Asia’s most entrenched political regimes and forced a reckoning with the country’s democratic future.

The February 12 elections were the logical culmination of that rupture. They were also the first real test of whether Bangladesh could reset its political system without sliding into chaos.

On the narrow question of electoral integrity, the answer appears to be yes. The polls were largely peaceful, competitive, and widely regarded as free and fair.

Security forces ensured order without visible interference. The interim administration under Prof. Muhammad Yunus delivered on its promise to restore credibility to the ballot. In a region where disputed elections often deepen political crises, Bangladesh managed something rare: A transition that did not spiral.

The results were decisive -- but this was not a zero-sum outcome.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) secured a two-thirds majority in Parliament. The Jamaat-e-Islami performed strongly, as did the newly formed National Citizen Party (NCP), born from the energy of the Monsoon uprising. Together, they command a substantial share of the popular vote and are positioned to serve as a meaningful opposition.

In that sense, almost every major actor can claim some measure of victory. The BNP won power. Reformist forces secured representation. Yunus preserved institutional credibility. The army maintained security and can now return to the barracks without overt political entanglement.

That alone makes this one of the most consequential elections in Bangladesh’s history. But elections are a beginning, not an end.

The Winner-Takes-All Trap

Bangladesh’s democratic setbacks have often followed moments of electoral triumph. In 2008, the Awami League won a two-thirds majority. Soon after, key democratic guardrails, including the caretaker system, were dismantled.

The pattern is familiar: Strong mandates are interpreted as permission to dominate, marginalize opponents, politicize institutions, and centralize authority. Over time, that cycle erodes trust and invites backlash.

This election carries that same risk.

Many voters were not simply choosing a party. They were seeking stability after months of unrest and uncertainty. They wanted predictability. They wanted a functioning government. But they did not vote for political vengeance. There are clear expectations.

The public does not want intra-party violence or factional rivalries spilling into the streets. They do not want politics used for personal enrichment or control. There is widespread fatigue with the idea that public office is a pathway to wealth accumulation.

Most importantly, voters do not want a return to “winner takes all” politics. Supermajorities can enable reform, but they can also silence dissent. If the BNP treats its two-thirds majority as exclusive ownership of the state, it risks repeating the mistakes that doomed its predecessors.

Tarique Rahman: Can the Politician Become a Statesman?

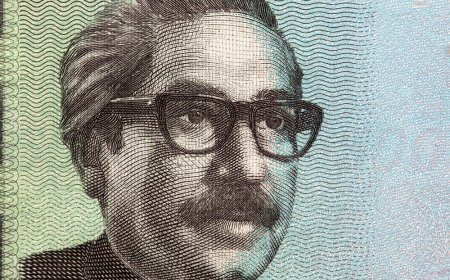

At the center of this new chapter stands Tarique Rahman. After 17 years in exile -- barred from speaking in local media and facing corruption allegations that his party says were politically motivated -- Rahman has returned at a moment of extraordinary expectation.

In his first interviews since coming back, he has struck a subdued tone. He acknowledged the personal costs of political struggle, including ongoing health challenges linked to past imprisonment.

In one interview, he framed his mandate clearly: “We will establish the power of the people. This is my commitment.”

He has coupled that democratic language with economic ambition, speaking of transforming Bangladesh into a trillion-dollar economy by diversifying beyond ready-made garments, expanding into IT, semiconductors, small and medium enterprises, and food production.

The vision is bold. But ambition must now be matched with restraint.

Statesmanship, in this moment, will not be measured by rhetoric. It will be measured by how power is exercised.

Structural Reform and the Discipline It Requires

The referendum on constitutional reform adds weight to the moment. Proposals such as creating an Upper House aim to rebalance executive authority and strengthen oversight. These are attempts to correct past excesses. But structural reform alone will not safeguard democracy. Process matters as much as outcome.

Reforms pushed through without consultation will look partisan. Reforms that exclude opposition parties, civil society, or youth voices will lack legitimacy. A two-thirds majority makes rapid change possible, but sustainable reform requires inclusion.

Depoliticizing the state apparatus will be an even more critical test. People are tired of the practice of filling administration, police, and state institutions with loyalists. Voters inspired by the July movement do not want to see one ruling party simply replace another across the bureaucracy.

Credibility could begin with simple steps: Public asset declarations by ministers and MPs, ending special privileges such as duty-free vehicle imports, reducing political control over local boards.

These are not radical reforms. They are trust-building reforms.

Justice Without Revenge

Transitions also bring temptation. Talk of “Truth and Healing” or reconciliation commissions must be handled carefully.

Indiscriminate cases, prolonged pre-trial detentions, or selective prosecutions would contradict the democratic aspirations that fueled the Monsoon uprising. If this new political chapter is to carry moral authority, it must reject revenge politics.

Accountability must be lawful, transparent, and fair. The same applies to media freedom, freedom of expression, and the right to organize. Without tolerance and protected dissent, electoral democracy remains fragile.

Will the Spirit of July Endure?

The most important question is not who won. It is how they will govern. Tarique Rahman has an opportunity to redefine his legacy - not simply as the heir to a political dynasty, but as a leader who stabilized and rebalanced the republic at a pivotal moment.

He faces real constraints. A trillion-dollar economy will require investor confidence, regulatory stability, and credible governance. Institutional reform and economic modernization cannot be separated.

If the BNP governs inclusively, strengthening parliamentary committees, empowering opposition oversight, protecting rights, and depoliticizing administration, Bangladesh could consolidate a competitive democratic system.

If it governs triumphantly, sidelining critics and concentrating power, public disillusionment could return quickly.

The Jamaat-e-Islami and the NCP also face a choice: Uphold the spirit of July through constructive opposition, or return to the scorched-earth politics that defined earlier decades.

The ousted Awami League remains unpopular. But political memory is not fixed. If new leaders fail to deliver stability and fairness, nostalgia can quietly resurface. Bangladesh has passed the electoral test. The country has shown that credible elections are possible. Power can change hands without collapse.

Now comes the harder test: Proving that victory does not mean domination, and that democracy is not only about winning elections, but about how winners treat those who lost.

That discipline, more than the vote itself, will determine whether this moment marks a durable democratic return, or merely the start of another cycle of upheaval.

Syed Zain Al-Mahmood is a journalist and communications consultant.

What's Your Reaction?