My Father’s Manila Folder and How Politics Lost Its Memory

IN a post-modern Bangladesh where everyone has their own truth and we have no shared history or experience, how do we come together to build the nation?

Hussain Muhammad Ershad is my favourite dictator because he was the first Bangladeshi autocrat whose fall I witnessed firsthand.

It was December 1990, I remember sitting with my brother in our Mohammadpur house watching my parents huddle around our TV set as news of Ershad handing in his resignation had just broken. It was as if the floodgates of democracy had opened.

Overnight, there was a cacophony of politicians making grand agendas, students reclaiming public spaces as their own, and journalists and editors taking up every space on media, which basically consisted of newspapers and our one TV channel BTV trying to analyze every new candidate or party that made a promise of a new beginning.

Back then, politics felt straightforward, almost innocent. Parties published manifestos that people actually read. Campaign rallies heralding elections focused on concrete policies: how many schools would be built, which roads would be paved, what subsidies farmers could expect.

My father would carefully compare these promises with past performances, sometimes going back a decade. "Look what they did last time," he'd say, pointing to newspaper clippings he kept in a manila folder. "Did they deliver on their word?" Politics was about track records, about holding leaders accountable to their previous actions. In our neighborhood tea stalls, heated debates would break out over shared realities, not Facebook personality cults or viral videos.

Social media didn't exist to fracture us into echo chambers. We consumed news from the same handful of newspapers and our solo television and radio channel. Facts felt like facts, even if we disagreed about what they meant. There was a shared reality we all operated within, naive as that might seem now.

Those days are gone. Sheikh Hasina, who ironically was once instrumental in the fight against my beloved dictator, followed Ershad’s path not primarily through manifestos or policy debates. Her fall was fueled by immediate experiences of oppression, by what young people could see and feel in their daily lives. Traditional party loyalties crumbled overnight because lived reality mattered more than historical allegiances.

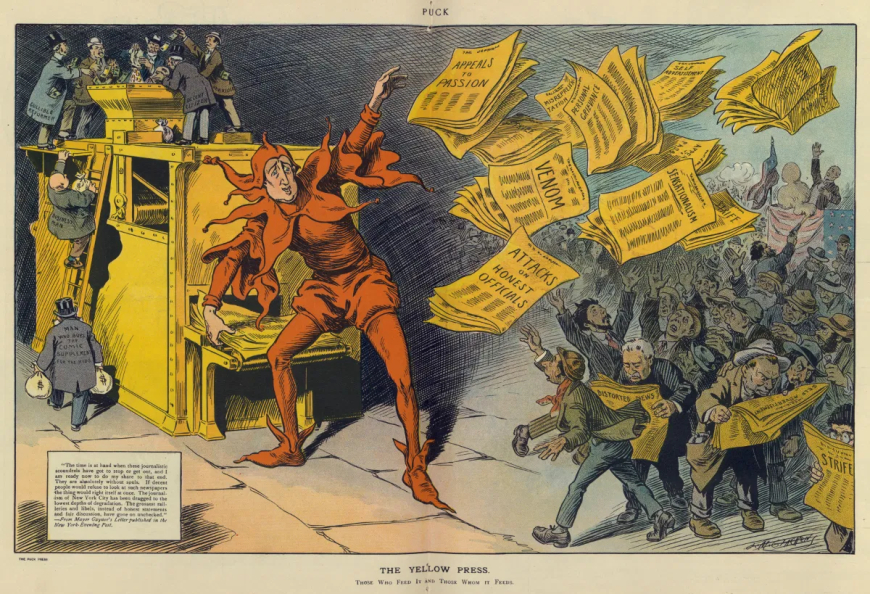

We've entered what scholars call a post-truth era, where conventional electoral rules like promises, manifestos, political records carry diminishing weight. Facts are no longer shared starting points for debate; they're contested territories where everyone stakes their claim to truth. My lived experience becomes my reality, and your lived experience becomes yours. There's no objective ground between us anymore.

This shift is reshaping democracy itself. In today's political landscape, what I observe personally carries more weight than historical data, expert analysis, or documented track records. If I see corruption in my daily life, that matters more than statistics showing decreased corruption rates. If I feel economically insecure, that trumps macroeconomic indicators suggesting growth. Personal viewpoints don't just shape how we interpret facts; they've become the facts themselves.

Social media amplifies this transformation. Algorithms feed us information that confirms what we already believe, creating separate realities for different groups. A young voter in Dhaka might see completely different "facts" about the same political party depending on which online spaces they inhabit. Truth becomes plural, relative, personal.

So what does this mean for Bangladesh's upcoming national elections? The implications are profound and unsettling.

Traditional powerhouses like the BNP face an unprecedented challenge. For decades, they've relied on historical legitimacy, party structures, and established narratives. But today's voters, especially young ones who drove last year's revolution, increasingly view big parties like the AL and BNP as indistinguishable. They've witnessed both acting with similar authoritarian tendencies when in power. Past achievements feel irrelevant when current experiences suggest continuity rather than change.

More strikingly, parties like Jamaat are successfully reinventing themselves despite their controversial historical baggage. Their documented opposition to Bangladesh's 1971 Liberation War, once considered an insurmountable political liability, no longer carries the same weight with younger voters. Why? Because today's electorate doesn't revere history the way previous generations did.

The past isn't sacred anymore. What happened fifty years ago feels distant and disputable compared to what's happening now. And what's happening now is that Jamaat and its student wing Shibir are perceived as pro-people and pro-transparency based on recent actions, not historical positions. Their participation in the anti-Hasina movement matters more than their role in 1971.

This represents a seismic shift in how political legitimacy gets constructed. Historical memory, once the foundation of political identity in Bangladesh, is losing its binding power. For many young voters at present, the Liberation War feels like ancient history, while corruption and authoritarianism feel immediate and personal.

But here's what worries me most about this transformation: when opinions completely override facts, when younger generations start dismissing history as irrelevant, we risk repeating the same mistakes over and over again. History isn't just about the past, it's our collective memory bank, helping us recognize dangerous patterns before they fully emerge.

Without historical anchoring, each generation becomes vulnerable to making the same errors their predecessors already paid for. We start believing that our current moment is entirely unique, that past experiences offer no guidance, that we can reinvent politics from scratch without consequence.

After an uprising that reminded me so much of those days back in 1990, Bangladesh is once again at the same crossroads. I think back to those evenings in our Mohammadpur home, when my parents believed that facts mattered, and history offered wisdom. Maybe they were naive. Maybe the world we live in now, where personal truth reigns supreme, is more honest about how politics really works.

But I can't shake the feeling that we're losing something essential when we abandon the idea of shared facts and collective memory. In our rush to embrace the immediate and personal, we might be forgetting the very lessons that could help us build a better future.

The question isn't whether we can return to those simpler days; obviously we can't. The question is whether we can find a way forward that honours both lived experience and historical wisdom, both personal truth and objective reality. A peek back into my father’s old manila folder might help getting that balance right.

Faruq Hasan is a development worker and a political analyst.

What's Your Reaction?