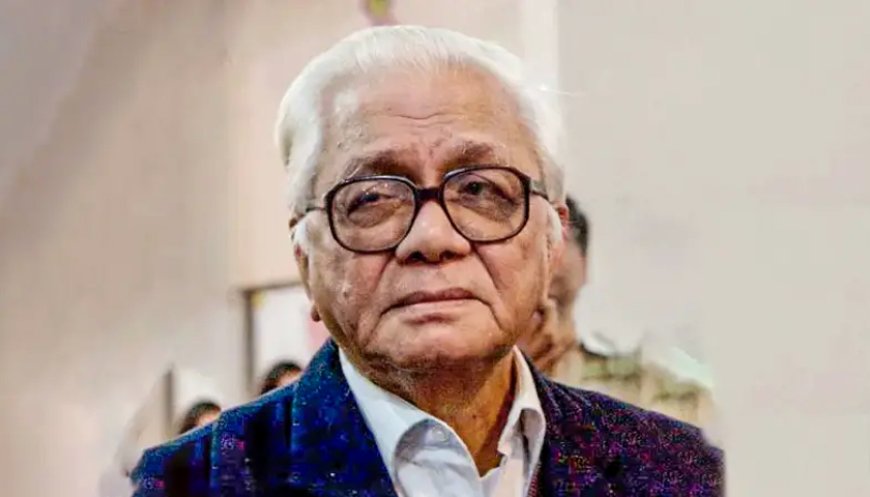

Keeping the Faith

Badruddin Umar was a giant of Bangladeshi letters. This remembrance outlines his scholarly and intellectual contribution without glossing over his limitations, and mourns the passing of a seminal thinker and historian.

Badruddin Umar (1931–2025), the leading scholar of Bangladesh’s Language Movement, recently passed away. Umar’s scholarly work on the Language Movement is widely recognized as a factually accurate, well-documented, objective, and balanced assessment of the movement’s events and personalities. That it is a significant and important contribution is generally acknowledged, even by scholars whose political and ideological views are opposed to those espoused by the late Badruddin Umar.

Umar was a prolific scholar. He was a smart and articulate polemicist who did his homework. Umar, born into a distinguished Bengali Muslim family in West Bengal, moved to Dhaka when his father, Abul Hashim (who was himself a political figure of considerable importance in pre-partition Bengal), decided to relocate to what was then East Pakistan in 1950. Umar’s Bengali accent and mannerisms retained a West Bengal tinge, even though he moved to the eastern part of Bengal in his late teens.

Umar studied philosophy at Dhaka University, but he subsequently obtained a BA in philosophy, politics, and economics (PPE) from the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. He chose an academic career, serving briefly as a lecturer at Dhaka University before joining the University of Rajshahi as the chair of its Department of Political Science (apparently, he also founded the Department of Sociology at the same university).

He was active in various ultra-leftist Marxist organizations and he stepped down from his academic post due to the university’s hostile environment in the late 1960s. However, these marginal political organizations that he joined were completely devoid of any significant following. Following the schism between the USSR and the People’s Republic of China, he sided with the Maoists or what in Bangladesh was known as the pro-Peking faction. He had disdain for the predecessor of the Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) and various pro-Moscow fellow travelers, mainly because of his dedication to Maoism, his anti-Soviet outlook, and his fears about an Indian regional hegemony.

Although Umar was involved in political activism, he will be remembered primarily for his scholarship and books, particularly those on the Language Movement, which show a serious and dedicated effort to carefully document the movement’s events and personalities, and explain the underlying political, economic, and social forces at play. His historical research pays careful attention to detail, with emphasis on accurately reporting the facts. While his analytical and ideological framework is that of an orthodox Marxist, he made a painstaking effort to objectively record the facts and the sequence of events. Even when his interpretation of events is grounded in his Marxist perspective, it provides refreshing and plausible insight, based on careful argumentation and evidence.

He was a shrewd observer of Bengali society with respect to culture, economic developments, class structure, and stratification, as well as a fierce critic of the Bengali ruling class’s opportunism. He made his mark in the 1960s with several remarkable books of essays on “communalism,” culture, and Bengali nationalism, among other topics. His book, “ভাষা আন্দোলন এবং তৎকালীন রাজনীতি” (The Language Movement and Politics at That Time), established Umar as the leading authority on the history of the Language Movement. In it, he argued that the movement for the inclusion of Bengali as an official language of Pakistani was not merely confined to students and the Bengali middle class but also had wider social and political backing. His subsequent research on the same topic further consolidated his reputation as a historian.

Umar wrote primarily in Bengali, but also occasionally in English. His Bengali prose was lucid and forceful, demonstrating a mastery of Bengal’s literary heritage. While Umar saw himself as a man of the left, his literary tastes, interests in poetry and literature, and cultural and musical preferences were based on an appreciation of high culture and literary masterpieces, both South Asian and Western. He could recite from memory both Bengali and Urdu poems.

Besides his work on the Language Movement, he wrote on political and economic developments in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and other developing countries. He was quite critical of non-government organizations (NGOs), operating in developing countries, such as Bangladesh. He denounced NGOs largely as a fabrication of Western donor agencies and the local bourgeoisie. He was reluctant to acknowledge the important role of NGOs in the improvement of economic and social indicators and their role in enhancing the poor’s well-being in Bangladesh.

It is remarkable and revealing that one of Umar’s books was polemically titled, Poverty Trade of Dr. Yunus. Umar was not just a polemist but he knew how to market and title his books, which sold remarkably well. That said, Umar was genuinely convinced that NGOs in Bangladesh and other developing countries were mostly inimical to the formation of class-in-itself and class solidarity. To his credit, Umar also called for the modernization and integration of Bangladesh’s education system.

Umar was not only a rather orthodox Marxist, but he remained an unreconstructed and unrepentant Stalinist-Maoist. Umar was well read, well informed, highly cultured, and a keen follower of international relations, global politics, and news. He followed developments in the Soviet Union and China quite closely. That Bengali Communists, such as Abani Mukherjee, Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, and Ghulam Ambia Khan Lohani, were ruthlessly murdered during Stalin’s purges would have been no secret to Umar.

Umar would have also known about the disastrous famine and starvation that occurred during China’s Great Leap Forward and later the cruelties and excesses of the Cultural Revolution initiated by Chairman Mao. Nevertheless, he did not touch upon the crimes of Stalinism-Maoism in a serious, credible, and conscientious manner in any of his voluminous writings. Surely this will remain a noteworthy blemish, even though Umar was an outstanding, hard-working, and detailed-oriented scholar with a knack for factual analysis and archival support in historical research on Bangladesh. Regarding his convoluted fancy for Maoism, there is nothing in Umar’s political and economic writings that showed any real, in-depth understanding of China’s important and remarkable transformation in the post-Mao era.

To his credit, Umar shunned the limelight and consistently refused state-sponsored honors, literary awards, pretensions, social events, and extravagance, though he was fond of good food and convivial conversations. He was an independent intellectual who remained committed to his beliefs and was not afraid of articulating his views openly, even when he was in a small minority. Umar was well respected by progressive intellectuals of his generation, as recounted by the moving elegies from Professor Rehman Sobhan and Dr. Rounaq Jahan, citing his intellect, independence, and human qualities.

If Umar is to be faulted, it is because some of his beliefs were quite erroneous: his lasting fidelity to Stalinism-Maoism was fundamentally wrong -- unjustified both politically and morally -- and he often failed to take a sufficiently self-critical view of his assumptions and beliefs.

Nevertheless, Badruddin Umar’s contribution to the history of the Language Movement has secured his place in Bengal’s intellectual history. His work will be widely read and valued in the years to come for its remarkable rigor, depth, and breadth. However, this voluminous scholarship will need to be critically evaluated to identify its limitations.

What's Your Reaction?