Reading Tarique Rahman’s Words

His BBC interview does not announce a new manifesto; it announces a new temperament. It marks the return not merely of a politician but of a political tone long missing in Bangladesh -- calm, composed, and confident in the people’s intelligence

In a nation long wearied by political noise and hostility, Tarique Rahman’s recent BBC Bangla interview arrived as something few expected -- a voice of calm, maturity, and reflection. After seventeen years in exile, the acting chairman of the BNP has re-emerged not as a fiery partisan, but as a contemplative statesman, conscious of time, circumstance, and transformation. The man once dismissed as a controversial figure now speaks with the poise of someone who has lived through exile’s long silence and returned with a vocabulary of restraint and reform.

Tarique’s words, for perhaps the first time, rise above the familiar grammar of political rhetoric. His tone is not combative, his arguments not laced with grievance, and his priorities not confined to his party’s traditional talking points. Instead, he speaks like a man who has seen the fragility of power and the futility of revenge. There is a sense of perspective -- a rare commodity in Bangladeshi politics -- that runs through every answer he gives.

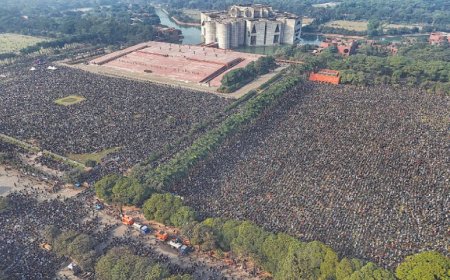

When asked about his role in the historic July Uprising that toppled a fifteen-year regime, Tarique refused to take personal credit. He called it a people’s movement -- a collective uprising that transcended party lines, professions, and generations. “The mastermind of this movement is the democracy-loving people of Bangladesh,” he said. In that single sentence, he shifted the focus away from himself to the public -- a symbolic gesture that distances him from the personality-driven politics that has long haunted the country.

This humility is striking. For decades, Bangladeshi politics has been defined by self-congratulation and cults of leadership. But Tarique’s refusal to glorify his own role, his insistence that students, labourers, women, and journalists all carried equal weight in that struggle, signals something deeper -- a rediscovery of collective agency in a society too long fragmented by party banners.

Exile has a way of maturing a man. Tarique Rahman left Bangladesh under dire circumstances -- physically broken, politically isolated, and legally silenced. Yet in his words now, there is neither bitterness nor denial. He speaks instead of connection -- of how, though absent physically, he has remained “mentally in Bangladesh for the past seventeen years.” That phrase alone captures a rare emotional honesty; it hints at both longing and commitment, at distance and belonging.

The interview reveals a politician who has observed his country from afar but never lost touch with its pulse. He acknowledges that Bangladesh has changed -- not just politically, but socially, psychologically, and technologically. He speaks of how COVID-19 altered the world’s thinking, how social media transformed human relationships, and how these forces have redefined politics itself. For a leader of a party often criticized for being trapped in the past, this recognition of change marks a crucial departure. He no longer speaks the vocabulary of 2001 or 2006; he speaks the language of 2025.

That awareness extends to his sense of responsibility. When confronted with questions about corruption allegations during BNP’s previous tenure, he neither deflected nor denied. Instead, he approached the issue with a mix of pragmatism and candour. He reminded the interviewer that when BNP took office in 2001, it inherited the governance failures of the previous administration. Yet he conceded that corruption, as a “social disorder,” could not be dismissed by political blame games. His emphasis on gradual, institutional correction -- “We will have to prove it with work” -- may seem modest, but it represents a maturity rare among leaders eager to promise miracles.

This is not the old Tarique Rahman of fiery declarations. This is a man who has learned that legitimacy cannot be reclaimed through anger; it must be rebuilt through accountability. Even when asked about allegations of misconduct by some BNP activists after the fall of the previous regime, his answer was layered with both responsibility and realism. He did not attempt to shield wrongdoers; he acknowledged that the party had taken disciplinary action against thousands, but reminded that “policing is not the job of political parties.” It was, he said, the duty of the government -- a subtle yet profound recognition of the boundaries between politics and state.

This separation of roles -- between political leadership and governance, between justice and vengeance -- defines the philosophical shift in Tarique Rahman’s tone. On the issue of accountability for past atrocities, he was unequivocal: those who ordered killings, disappearances, and torture must face justice. But he made it equally clear that “this is not a matter of revenge, it is a matter of law.” In a political landscape where retribution has often replaced reconciliation, that distinction matters.

Even his comments about his long-time rival, the Awami League, were measured. He did not advocate bans or exclusion; instead, he placed faith in the people’s verdict. “If the people do not support a party that kills, disappears, and loots, I see no reason for it to survive,” he said. That is not an act of hostility but of democratic confidence -- a belief that popular sovereignty, not institutional suppression, should determine the fate of political parties.

What also stands out in this conversation is Tarique’s redefined view of electoral politics. His approach to candidate selection -- prioritizing local connection, credibility, and public trust over money or family -- suggests an effort to restore integrity to a process long tainted by patronage. His assurance that BNP will “nominate those who have the support of all people of the area, not just the party” is as much a message to voters as it is to his own organization.

Equally significant is his stance on coalition politics. Rather than rejecting parties like Jamaat-e-Islami outright or rushing into alliances for expedience, he grounded his answer in principle: anyone operating within the Constitution has the right to participate in politics. This is not naivety; it is pluralism -- a recognition that democracy, however fractured, must accommodate differences rather than erase them.

His reflections on his family’s suffering -- the loss of his brother, the imprisonment and illness of his mother, the destruction of his home -- could have been an opening for emotional manipulation. Yet Tarique refused to weaponize pain. He turned personal tragedy into empathy, saying that his story mirrors those of thousands of Bangladeshi families who lost loved ones or livelihoods to injustice. It was a moment of profound humanization -- the voice of a man who has suffered but no longer speaks from the wound.

Even his remarks on the student elections at Dhaka University were unusually sober. He saw the exercise not as a political barometer but as a “good start for the democratic journey,” showing restraint instead of opportunism. That moderation -- resisting the urge to overclaim or overreact -- lends his words a credibility that politics in Bangladesh desperately needs.

There is, too, an implicit awareness that leadership today demands a new kind of communication. His reliance on reason over rhetoric, his willingness to say “I don’t know” or “time will tell,” and his refusal to assign blame impulsively all suggest a leader more interested in persuasion than provocation. He is redefining what it means to sound like a statesman in a country where shouting often substitutes for speaking.

Tarique Rahman’s BBC interview does not announce a new manifesto; it announces a new temperament. It marks the return not merely of a politician but of a political tone long missing in Bangladesh -- calm, composed, and confident in the people’s intelligence. His repeated affirmation that “the people are the source of all power” reclaims BNP’s foundational philosophy, which had over time been buried beneath anger and resistance.

It is too early to say whether this new tone will translate into new politics. Bangladesh’s landscape remains volatile, its institutions fragile, its voters skeptical. Yet in Tarique’s words lies a rare possibility -- that leadership in Bangladesh can evolve from domination to dialogue, from vengeance to vision. His emphasis on justice, inclusion, and collective responsibility offers a glimpse of a politics that could once again belong to citizens rather than parties.

The man who once carried the burden of controversy now carries the weight of expectation. But if this interview is any indication, Tarique Rahman’s long exile may have been less a retreat than a period of reflection -- a time that tempered impulse with insight. His tone, his reasoning, and his restraint together signal not just his own political reawakening, but perhaps the first stirrings of Bangladesh’s as well.

H. M. Nazmul Alam is an Academic, Journalist, and Political Analyst based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Currently he is teaching at IUBAT. He can be reached at [email protected].

What's Your Reaction?