Why So Serious, NCP?

Politics is not a moral monastery. It’s a battlefield of imperfect allies and temporary truces. If the NCP keeps attacking everyone around it, soon it will have no one left to fight beside. Reform may begin with rebellion, but it survives through relationships. And without those, no revolution lasts long enough to write its own constitution.

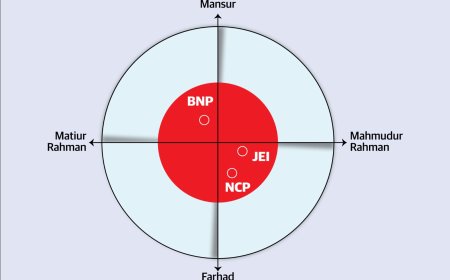

Politics in Bangladesh often resembles a crowded family dinner -- everyone claims to want the same thing, yet spends the evening arguing about who cooked the rice wrong. The latest quarrel in this political feast is between the National Citizens Party (NCP) and Jamaat-e-Islami, with the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) watching from across the table, pretending to sip its tea in peace.

The bone of contention? A piece of paper called the July Charter, which was supposed to be the grand symbol of “national unity,” but has instead become a playground for bruised egos, ideological insecurities, and some spectacular displays of political self-righteousness.

The NCP, a relatively new entrant that claims to speak for the disenchanted youth, has spent the last few days doing what all good reformists do -- scolding everyone else. Its convener, Nahid Islam, called Jamaat’s ongoing movement a fraud, dismissed its push for proportional representation (PR) as political deception, and accused it of sabotaging the national reform dialogue. One might have mistaken the tone for a national emergency, but it was, in truth, the familiar sound of one minor party trying to punch above its electoral weight.

The irony is almost poetic. The NCP, which did not even sign the July Charter, is now waging a rhetorical war against those who did. Its frustration seems rooted in being left out of the big boys’ club -- the 25 parties, including BNP and Jamaat, that signed the Charter after long hours of dialogue with the Consensus Commission. The NCP’s refusal to sign, it seems, was meant to be a show of moral superiority, a grand gesture of ideological purity. Unfortunately, moral superiority rarely wins elections.

One can sympathize with their disappointment. In a political field dominated by veteran survivors of coups, crackdowns, and compromise, the NCP’s youthful zeal for “state reconstruction” looks fresh, even idealistic. But idealism, when mixed with arrogance, can be toxic. The NCP seems to have mistaken its self-imposed isolation for intellectual depth. Like a student who skips group work to write a solo essay on the meaning of teamwork, the party appears proud of standing alone — while others get on with the messy business of politics.

It is, however, fascinating how fast “reform” in Bangladesh becomes a code word for factional posturing. Jamaat’s version of reform is to introduce PR in the lower house, which it believes would give smaller parties a fairer share of parliamentary representation. The NCP, on the other hand, wants PR only in an upper house that does not yet exist -- a body it envisions as the guardian of constitutional morality. Both sound visionary on paper, but in practice, one is a nostalgic dream of European parliamentarism, and the other, a theoretical exercise with no practical roadmap.

The problem is not that these visions differ; it’s that they compete for moral legitimacy rather than political efficacy. The NCP brands Jamaat’s movement as fraudulent because it thinks Jamaat’s version of reform dilutes the revolutionary purity of the July Charter. Jamaat, in turn, calls NCP’s attitude childish. And BNP, ever the elder sibling, smiles quietly, pretending to be above the squabble, while keeping both camps within reach -- just in case.

Underneath all this is a deeper question: what exactly does the NCP want? Its statements oscillate between moral fury and political confusion. It claims to fight for a new constitutional order, to establish a Constituent Assembly, and to reconstruct the state in light of the “people’s uprising.” But none of that clarifies how it plans to contest elections, form a government, or even secure a few seats without the logistical and electoral backup of BNP or Jamaat. For a party still trying to establish its footprint, alienating potential allies before the first ballot is cast is not political courage -- it’s strategic suicide.

Politics, after all, is not a university debate on purity. It’s the art of compromise. BNP, despite its own flaws, understands that reform without power is just poetry. Jamaat, for all its baggage, knows that political participation requires flexibility. But the NCP seems to think that purity can substitute for popularity, and moral outrage can win votes. It cannot. Without organizational muscle, grassroots networks, or regional influence, the NCP’s lone march for reform risks becoming a social media crusade rather than a national movement.

What’s even more puzzling is the NCP’s insistence on portraying Jamaat’s reform drive as “strategic infiltration.” Such language may satisfy the party’s rhetorical appetite, but it only exposes insecurity. Every young party eventually faces the temptation to define itself by who it is not. The NCP seems to have fallen into that trap early -- defining itself through negation, not proposition. Its speeches are full of what it won’t do, who it won’t ally with, and which movements it won’t join. What it will do remains shrouded in abstraction.

For a party that aspires to represent the youth, this approach is particularly self-defeating. The youth of Bangladesh are indeed disillusioned -- with corruption, dynasty politics, and the perpetual theatre of betrayal. They crave fresh leadership, but they also crave results. They want to see a party that can navigate the system without becoming a hostage to it. By spending more time criticizing others than mobilizing support, the NCP risks sounding like the political version of an angry Facebook commentator -- eloquent, indignant, and ultimately irrelevant.

Then comes the question of tone. The NCP’s language, invoking “fake reformists,” “fraudsters,” and “morally bankrupt forces,” might appeal to its core supporters, but it alienates the undecided middle ground -- the very citizens it claims to represent. Politics is not therapy, and outrage, no matter how articulate, is not strategy. The NCP must decide whether it wants to be a movement of moral resistance or a player in the real arena of power. Because right now, it sounds like a reformist puritan standing at the gate of democracy, scolding everyone inside for not being sincere enough.

And yet, one cannot deny that the NCP has touched a nerve. Its critique of symbolic charters and performative unity is not entirely baseless. The July Charter indeed suffers from a lack of clear implementation mechanisms. Many of its signatories view it as a political necessity rather than a genuine reform blueprint. In that sense, the NCP’s skepticism reflects a legitimate frustration with Bangladesh’s pattern of reform without enforcement. But that frustration, if not channelled into constructive coalition-building, risks isolating the very people capable of making reform happen.

In the end, the NCP’s greatest enemy may not be Jamaat or BNP -- it may be its own self-importance. There’s a fine line between principled dissent and performative defiance. Crossing it turns reformers into cynics and allies into adversaries. The NCP must ask itself a simple question: does it want to win the argument or win the country?

If it truly wishes to reshape the political landscape, it must learn to engage without moral contempt. Politics in Bangladesh is messy by design; no one gets to stay clean for long. To insist on absolute purity is to renounce participation altogether. And a reformist who refuses to participate is like a preacher without a congregation -- righteous, but alone.

The NCP’s slogan may be about citizens, but its behavior risks alienating those very citizens by projecting elitist disdain toward political pragmatism. Without the electoral scaffolding of BNP or the street networks of Jamaat, the NCP’s lofty dreams of constitutional reconstruction may remain confined to press releases and passionate Facebook posts.

So why so serious, NCP? Politics is not a moral monastery. It’s a battlefield of imperfect allies and temporary truces. If you keep attacking everyone around you, soon you’ll have no one left to fight beside. Reform may begin with rebellion, but it survives through relationships. And without those -- without sustainable, strategic, and even occasionally uncomfortable alliances -- no revolution lasts long enough to write its own constitution.

Perhaps it’s time for the NCP to learn that humility, not hostility, builds nations.

H. M. Nazmul Alam is an Academic, Journalist, and Political Analyst based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Currently he is teaching at IUBAT. He can be reached at [email protected].

What's Your Reaction?