The Riddle of Shrine Attacks: Why Intra-Muslim Violence Surprised Us

To protect shrines is to protect a vision of Islam that is inclusive, creative, and rooted in ordinary life. The riddle of the shrine attacks is solved only when we see that the real threat is not just the loss of Hindu-Muslim peace, but the erosion of Muslim-Muslim coexistence.

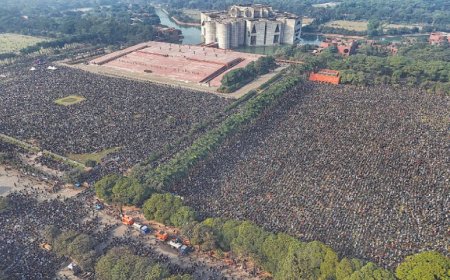

After August 5, 2024, Bangladesh entered a new political chapter. The fall of the Hasina regime, brought about by a spontaneous uprising of students and ordinary citizens, was widely seen as a moment of liberation from years of authoritarian rule. Commentators at home and abroad, however, warned that such upheaval could unleash communal violence. Their fear was clear: Hindus might once again become the target of reprisal.

The logic seemed simple and familiar. In Bangladesh, when politics turns violent, minorities often bear the brunt. Yet what unfolded after August 5 defied that expectation. Instead of a major Hindu-Muslim conflagration, the country saw a surge of attacks on shrines, khanqahs, and dargahs -- spaces that have long stood at the heart of Muslim devotional life.

The numbers tell part of the story. By January 2025, police admitted that at least 44 attacks on 40 shrines had taken place across Bangladesh (The Business Standard, The Daily Star). But Sufi leaders and independent monitors reported a much higher toll: the US Commission on International Religious Freedom noted that around 80 shrines had been attacked since July 2024 (USCIRF Factsheet).

Since then, the violence has only escalated. Reports now put the total at more than 100 shrines targeted nationwide since August 5, 2024. In Rajbari, for example, attackers desecrated Nural Pagla’s shrine -- digging up the saint’s grave, setting it on fire, and leaving nearly 50 people injured, including police (Prothom Alo). In Comilla, four shrines were attacked in Homna, prompting a single case against more than 2,200 accused persons (The Business Standard).

Hindu-Muslim tensions did flare in this period, but they never reached the scale or persistence of the sustained assaults on Sufi shrines. The question remains: why did so few anticipate that the most significant wave of post-August 5 violence would take the form of intra-Muslim sectarianism? And why was the imagination of religious conflict so fixated on the Hindu-Muslim divide while Sufi shrines burned?

The truth is that intra-Muslim tensions are not new. The Sufi order, with its shrines and devotional practices, has long been a lightning rod for criticism from reformist currents -- whether Deobandi, Salafi, or political Islamist. For decades, Sufi practices have been condemned as bid‘ah (innovations) or even as veering into shirk (associating partners with God). What changed after August 5 was the sudden collapse of social and political control. In that vacuum, groups and individuals who harbored resentment against Sufi traditions found an opportunity to act.

Shrines are symbolically powerful but materially vulnerable. They represent the living heart of popular Islam, drawing men and women, rich and poor, Muslims of every stripe to celebrate saints’ legacies.

By contrast, most mosques in Bangladesh, while community-run, are closely aligned with dominant and orthodox forms of religion, and many are connected to socially and politically influential groups. Any attack on them would provoke immediate and widespread outcry. Major mosques in Dhaka or divisional towns, for instance, often enjoy the backing of powerful networks of business leaders and political elites, making them virtually untouchable.

Shrines, on the other hand, are less connected to these national power structures. They often lack organized protection and enjoy fewer ties to the country’s dominant political or religious establishments. This distance makes them easier to target in times of upheaval. Attacking a shrine is not just a physical act -- it is a declaration, a way of inscribing a orthodox reformist vision of Islam onto the landscape. In this sense, the violence was directed at a religious-symbolic order, an attempt to erase Sufi practices deemed un-Islamic.

Their vulnerability was heightened after August 5 2024 for another reason. Sufi shrines have historically kept a certain distance from overt national politics, preferring to anchor themselves in spiritual and community life. That reluctance to participate directly in partisan struggles, however, made them convenient scapegoats in the volatile aftermath of political change. For some, accusing the shrines of complicity with the ousted Hasina regime became a way to rationalize attacks, even when no such ties existed.

Yet to describe shrines as politically marginal is not to say they lack influence altogether. Many are deeply woven into local social and cultural life -- through festivals, donations, charitable work, and community gatherings -- that shape everyday life in villages and towns. This embeddedness gives shrines a kind of grassroots authority, which can be resented by rival groups seeking to consolidate their own power. To strike at a shrine, then, is not only to denounce Sufi practices but also to weaken a competing source of community legitimacy. In this way, the violence was simultaneously about theology and about reordering power -- a struggle to redefine both religion and politics in a chaotic time.

The Overlooked Face of Religious Conflict

The riddle, then, is not simply why shrines were attacked, but why so few imagined this possibility. One reason lies in the way Bangladesh’s intellectual and political elites often speak of Islam as if it were a single, unified block. Diversity within Islam -- between Sufis, reformists, and traditionalists -- is acknowledged in specialist scholarship, but rarely enters the language of politics or the mainstream press. This creates a dangerous blind spot: when violence erupts along these internal lines, it appears sudden, even though the tensions have been simmering for decades.

Another reason is the long shadow of Hindu-Muslim violence. From colonial census categories to Partition, from the war of 1971 to more recent episodes of anti-Hindu attacks, communal riots have left deep scars that continue to shape how we imagine religious conflict. Journalists, activists, and international observers are right to remain vigilant about this danger, because it has repeatedly erupted with devastating consequences. Yet this very vigilance has also narrowed our field of vision. It meant that when shrines and dargahs were attacked, the violence seemed unexpected -- not because communalism is less urgent, but because sectarian hostility within Islam had never been anticipated with the same seriousness.

This failure of anticipation matters. Because we are more aware of Hindu-Muslim clashes, our institutions, advocacy, and legal frameworks are geared toward them. By contrast, sectarian violence within Islam rarely receives the same recognition or preparation, even though its consequences can be just as destabilizing. Overlooking it not only leaves communities like the Sufis unprotected but also reinforces the myth of a monolithic Islam -- precisely the myth that sectarian actors seek to impose through violence.

Rethinking Religious Infighting

If shrine attacks seemed unforeseen, it is partly because we have not learned to treat sectarian violence with the same urgency as Hindu-Muslim clashes. Yet their impact is no less corrosive. Sectarian infighting fractures Muslim communities from within, delegitimizes deeply rooted devotional traditions, and narrows the horizons of religious life in Bangladesh. By targeting shrines, reformist groups are not only waging a theological battle but also attempting to erase forms of Islam that have long anchored cultural and communal belonging.

Recognizing this threat does not diminish the importance of protecting Hindu minorities. Rather, it highlights that pluralism in Bangladesh rests on two fronts at once: between faiths, and within Islam itself. To defend only one while ignoring the other is to leave the country’s religious landscape dangerously exposed.

The persistence of Sufi shrines, and their enduring popularity among ordinary Muslims, reminds us that Islam in Bengal has never been monolithic. Violence against them does not demonstrate the strength of reformist visions but their insecurity. A confident theology does not need to set fire to shrines; only an anxious one does. What is at stake, then, is not merely the survival of a ritual tradition but the preservation of a plural Islam that has always been integral to Bengal’s religious fabric.

Toward a Response

What, then, is to be done? Protection of shrines is one immediate need. Police deployments and legal cases matter, but they are not enough. Security can only address the symptoms, not the deeper problem. Equally important is the recognition of Sufi heritage as part of Bangladesh’s cultural identity -- something to be celebrated in schools, in the media, and in national narratives. These traditions are not peripheral curiosities; they are central to the story of Islam in Bengal, and their erasure would mean the loss of a living archive of pluralism.

A wider response must also come from intellectual and civic voices. Scholars, journalists, and activists need to challenge the habit of framing religious conflict solely through the lens of Hindu-Muslim clashes. Defending pluralism requires vigilance against sectarian exclusion as well. If the intellectual class fails to speak to this danger, the public imagination will remain captive to a narrow understanding of religious violence, leaving Sufi communities vulnerable.

At the same time, community-level resilience is crucial. Local networks of devotees, cultural groups, and religious leaders can play a role in protecting shrines by affirming their place in the everyday life of Bangladeshis. When shrines are defended as shared spaces of devotion, charity, and memory, they become harder to isolate as targets.

Ultimately, the solution lies in embracing pluralism not as a slogan but as a lived reality. To protect shrines is to protect a vision of Islam that is inclusive, creative, and rooted in ordinary life. The riddle of the shrine attacks is solved only when we see that the real threat is not just the loss of Hindu-Muslim peace, but the erosion of Muslim-Muslim coexistence. If Bangladesh cannot defend both, it risks losing the very diversity that has long been its strength.

Ahmad Sabbir Ahmad, PhD Candidate in Anthropology at McGill University. His research focuses on religion, politics, and pluralism in South Asia.

What's Your Reaction?