The Ballad of the Missing Bullets

Each missing gun is a potential shooting at a street corner, a robbery, a killing. As national elections approach, the fear is not hypothetical. It is Chekhov’s gun multiplied by a thousand: if a weapon hangs on the wall in Act I, it must go off by Act III. And Act III is the election.

If Bangladesh were to pitch its current law-and-order saga to HBO or Netflix, the producers might laugh it off as “too unrealistic.” After all, who would believe that thousands of government-issued weapons could be looted in broad daylight, that hundreds would remain missing more than a year later, that criminals would carry state-engraved rifles to commit extortion, and that the only innovation from the authorities would be a cashback offer for returning the guns? It sounds like satire. The problem is, it isn’t. It’s the evening news.

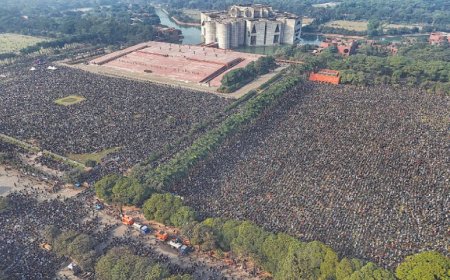

On August 5 last year, mobs attacked 460 police stations and 114 outposts across the country, looting 5,753 weapons and over 652,000 rounds of ammunition. They even helped themselves to 31,000 tear gas shells, 4,700 sound grenades, and a few hundred color smoke grenades -- enough to stage a rock concert, except the performers are criminals and the audience is terrified. Police headquarters later admitted that 4,410 weapons and about 394,000 bullets have been recovered. That still leaves 1,353 weapons and 257,659 bullets missing. The unrecovered arsenal includes pistols, rifles, shotguns, light machine guns, gas guns, tear gas launchers, and even handheld tear gas sprays -- because nothing says “complete breakdown of order” quite like gangsters carrying police-issue tear gas on their evening rounds.

Numbers alone tell the story. Out of 1,106 Chinese rifles, 991 have been recovered. Out of 539 pistols, 325. Out of 1,092 pistols of another model, 630. Out of 589 gas guns, 458. Out of 15 tear gas launchers, only 8. And so on, until one realizes that the missing inventory could equip several platoons. Enough to turn a gang fight into a small war.

These weapons have not disappeared into a void. They have “changed hands” -- a polite phrase meaning they now belong to top underworld figures, notorious terrorists, escaped convicts, and political cadres who treat firearms as both livelihood and election campaign material. In Dhaka, shootings in Badda, Mohammadpur, and Mirpur in recent months have left people dead or robbed of lakhs.

In Chittagong, a businessman’s house came under armed attack after he refused to pay extortion money, the assault captured neatly on CCTV. In Munshiganj, a young woman was murdered with a pistol looted from Wari Police Station. Police themselves admit that criminals have used the missing weapons in robberies, extortion rackets, and targeted killings. It is one thing for illegal arms to circulate underground; it is another when they come stamped with “BD Police.”

In some cases, criminals have been arrested and looted arms recovered. But the plot twist worthy of House of Cards is that members of the police have themselves been implicated in selling these weapons. It is one thing when law enforcers fail; it is another when they moonlight as arms dealers. Shakespeare might have updated Hamlet: “Something is rotten in the state of Bangladesh, and it carries a serial number from the armory.”

The government’s solution has been to announce rewards. A pistol will fetch Tk 50,000, a rifle Tk 1 lakh, a submachine gun Tk 150,000, and an LMG Tk 5 lakh. Ammunition earns Tk 500 per bullet. The policy sounds less like a national security measure and more like a Black Friday sale. One imagines criminals calculating: keep the SMG that earns millions from extortion, or trade it for Tk 150,000 and a handshake? Keep the bullets for the next robbery, or sell them for less than the price of a buffet in Gulshan? In effect, the government has turned recovery into a reality show, where contestants bid for guns like in Pawn Stars.

Behind the absurdity is a serious danger. Each unrecovered weapon is not just a statistic. It is a potential shooting at a street corner, a robbery, a killing. As national elections approach, the fear is not hypothetical. In Bangladesh, elections have never been entirely free of muscle and violence. This time, the muscle comes equipped with government-issued rifles. It is Chekhov’s gun multiplied by a thousand: if a weapon hangs on the wall in Act I, it must go off by Act III. And Act III is the election.

The problem is compounded by the jailbreak of the same fateful August. Some 2,200 prisoners escaped, 700 remain on the run, including 69 militants and death-row convicts. Many are suspected of having acquired looted weapons. So, along with local goons and political cadres, escaped convicts now roam the streets with state arms. If this were a video game, it would be Grand Theft Auto: Dhaka Edition.

Security experts have been blunt. Unless drastic measures are taken -- combing operations, army deployment, real intelligence work -- the weapons will continue to fuel criminal networks. But tactics alone are not enough. The deeper issue is institutional. Criminals do not loot thousands of weapons and keep them for over a year unless the system is deeply compromised. And no amount of “Operation Devil Hunt” or “joint drives” will succeed if the very institution tasked with recovery is leaky at the core.

The irony is hard to miss. When it comes to students protesting tuition fees or opposition activists chanting slogans, the police can deploy entire battalions overnight. When their own guns vanish, they transform into a cast from Where’s Waldo, endlessly searching but never finding. This selective efficiency is not just incompetence -- it is complicity by omission.

It is also a question of priorities. The missing arsenal has become a thorn in the side of the people, as the report rightly said, but apparently not enough of a thorn for urgent recovery. Citizens are left to wonder: if the police cannot safeguard their own weapons, how will they safeguard ordinary lives? If they cannot trace their own pistols, how will they trace criminals? If criminals commit crimes with police-issued rifles, who is really in charge -- the police or the criminals?

The normalization of absurdity is perhaps the greatest tragedy. A year after the looting, the public is expected to accept the unrecovered 1,353 weapons as a mere footnote. Rewards have been announced, a few arrests made, and the rest filed under “in progress.” It is as if the country has internalized the farce: that weapons may be stolen, used for murder, even sold by policemen, and yet the system shrugs and moves on. For citizens, however, there is no shrug. Every unrecovered weapon is a reminder that their safety is negotiable, their security conditional, their lives collateral.

The curtain may never close on this story. Perhaps more weapons will be recovered, perhaps not. Perhaps some will turn up in election violence, others in robberies, others buried and forgotten. But as long as hundreds of guns and hundreds of thousands of bullets remain in criminal hands, Bangladesh lives in a theater where the villains carry the props, the heroes lose their lines, and the audience cannot leave. It is a tragicomedy, but for the people, there is nothing funny about it.

H.M. Nazmul Alam is an academic, journalist, and political analyst. He can be reached at [email protected].

What's Your Reaction?