Whatever Happened to the Bangladeshi Elite?

Are there signs that the old elite consensus that governed Bangladesh for five decades is breaking down, and, if so, what will replace it?

The Old Elite Consensus

It seems unbelievable in these days of viciously polarized politics, but for decades a defining feature of the Bangladeshi elite was its high degree of consensus on matters of vital importance to the nation.

Of course there were public spats between political leaders, and constant battles over who should run the country. But the people with political or administrative or financial power, the people whose ideas and actions were influential, agreed on some basics: that Bangladesh needed to develop if it were to drag itself out of poverty, and that meant committing to the pursuit of economic growth, investing in the country’s only real resource and the source of its comparative advantage -- its large population -- and focusing assistance on the poorest, including through space for Bangladesh’s innovative social organizations.

You can see the contours of this ‘elite bargain’ if you look at the policies of all the regimes after the ill-fated first Awami League government. You will note a striking convergence on economic liberalization, policies to promote manufacturing exports, education for all, disaster response, and food security.

No government abandoned the overall thrust of moderately pro-poor economic development. Although people routinely complained that each incoming government meant new policies, the changes were typically symbolic in nature. Relatively minor revisions in which sectors were favoured and which public servants got a raise and the names of airports or roads overlaid a sameness in the general direction of policy.

No doubt the initially high degree of aid dependence played a role in this, as Rehman Sobhan has observed. But the stable economic growth and improvements in human development indicators through the 1990s and much of the 2000s testified to this steadiness, this elite consensus on what the country needed and how it should be brought about.

I have been thinking about the Bangladeshi elite recently, partly because of the viciously polarized and personalized politics of the moment, and what that presages for the next few decades. But it has also been 20 years since I published my first book, Elite Perceptions of Poverty in Bangladesh1 -- a political-sociological study of how the people with disproportionate power over institutions and ideas in Bangladesh viewed the challenge of mass poverty.

Based on my doctoral research in the late 1990s, the argument was that this comparative consensus owed in part to the composition of the elite itself. Compared with the elites of many other countries, Bangladeshi elites were a relatively homogenous group, mostly Bengali-speaking Muslims from the relatively fluid middle and upper middle classes, with close ties to the rural majority. As is the case with other national elites, they were educated together and married each other, so even across mutually-hostile political groupings there were often close familial ties.

This internal homogeneity but also their affinity with the masses (it must be stressed, in comparison to other better-entrenched and more hierarchical elites) were reasons for this consensus. Another was that the facts of Bangladesh’s underdevelopment had been laid bare by the brutal decade of the 1970s, with the devastating Bhola cyclone, the war and its aftermath, and the 1974 famine, the last crisis of which Mohiuddin Alamgir estimates killed at least 1.5 million people.2

The problems were painfully clear; the solutions ranged across a narrow band of options within the confines of international political economy, aid dependence, and limited natural resources.

If an elite consensus underpinned Bangladesh’s development successes in the 1990s and 2000s, what are we likely to see in this emerging political settlement?

Will a similar consensus enable enduring support for the policies likely to be needed for the second quarter of this turbulent 21st century?

Will the Bangladeshi elite be united behind meaningful efforts to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate crisis?

Will they present a united front in negotiations for the Loss and Damage funds so valiantly fought for by our very own much-missed Saleemul Huq?

Will they put aside their differences to diversify the economy beyond dependence on the cheap labour model of export manufacturing and remittances?

Will they agree enough on the rules of the political game to enable Bangladeshis to live peaceful and productive lives?

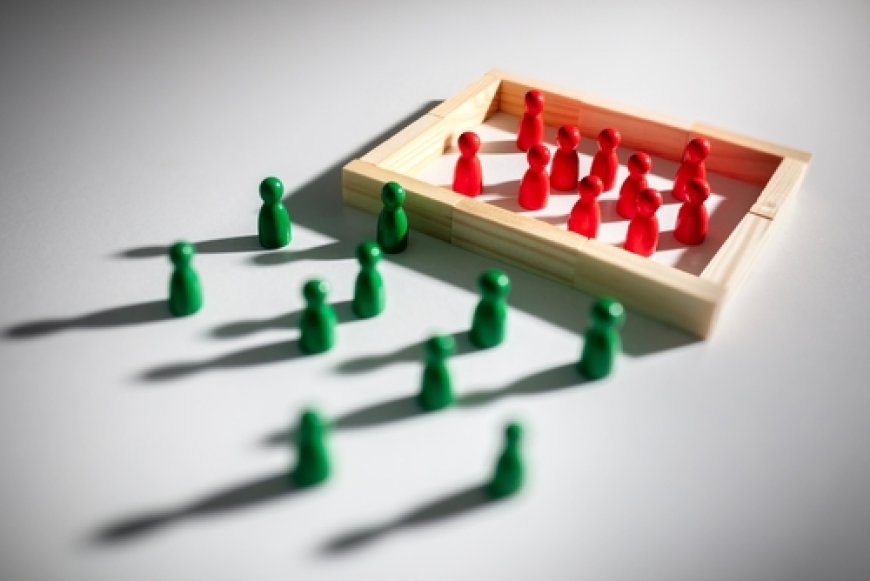

None of this seems certain at this time. The Bangladeshi elite, like many other elites the world around, are not so much polarized as they are fragmented, emergent, and in disagreement about where the country needs to go and how it should get there.

When we did our comparative study of elite perceptions of poverty and inequality in the 1990s, we were motivated by the idea that political and policy agendas to tackle poverty in the now-advanced welfare states of the North had been shaped by elite perceptions that the poor posed a threat through crime, insurrection or contagion that could be mitigated or prevented through concerted state action.

Could similar threats be detected in the perceptions of the national elites of Bangladesh, Brazil, or South Africa (among others)? Not, it turned out in Bangladesh. There was no great fear that poverty would lead to either mass crime or insurrection, and even into the 1990s, epidemics were not a source of threat from the masses of the Bangladeshi poor. The crime of the poor were, if anything, forgivable on grounds of natural law.

A retired state official said: "If I steal some food to feed my son, and if I take crores and crores of taka from the government, which one is the criminal? Rich people are mostly criminals, most of them are criminals, poor people are not really criminals."

It was not that crime was not a threat, but the threat did not emanate from poverty but from power.

Insurrection was similarly not a major concern, in part because elites believed that the modest efforts to assist the poorest curbed revolutionary appetites, but perhaps also because political parties of the left have been weak and coopted since the febrile post-independence days, after violent suppression by successive regimes through the 1970s.

And while the Bangladeshi elite stand out from their counterparts in other countries in that they live among the poor (contrast the gated communities of Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town with cheek-by-jowl Dhaka), the threat from epidemics spreading from low-income communities was never real.

When COVID19 struck in 2020, it was imported from abroad, and the cosmopolitan upper and middle classes were the more likely vectors of the disease, at least to begin with.

The Bangladeshi elite of the 1990s also had limited faith in the state; knew it lacked capacity; had absorbed many of the neo-liberal precepts about markets being more effective at the distribution of scarce resources, and were open to NGO action for what remained to be done to protect the most vulnerable. "Government cannot feed everyone" was a line I heard on several occasions, in support of arguments against the possibility of a welfare state.

New Elites, Different Times

As Bangladesh rebuilds its political settlement after the Bloody July uprising, it is time to revisit the foundations of the policy consensus. How have the policy perceptions of the Bangladeshi elite changed since the 1990s?

Partly the answer depends on how the character and composition of the Bangladeshi elite have changed. There are undoubtedly more very rich people in Bangladesh than in the 1990s, and their wealth gives them individual and collective sway.

Economic growth from the key sectors such as garments, "manpower," property, energy, and finance (including a possible $10-15 billion looted from the public finances3) has created an entire new class of the super-wealthy.

In 2020, the wealth analytics firm Altrata estimated that in the decade 2010-19, Bangladesh had been the country with the fastest growth rate of Very High Net Worth Individuals or people with a net worth of between $5 million and $30 million; their numbers had grown over 14% annually over that period, albeit from a low base.4

By 2021, there were over 2,700 such individuals,5 and we can expect that their discoverable wealth is not all there is to count. In size, this remains a small class of the very rich compared to other countries; but the speed of its growth and its emergence as a distinct class fraction of the conspicuously world-class rich are likely to have changed how these people live in, relate to, and think about the majority and the future of the nation.

The signs of wealth are evident from luxe lifestyles that were unimaginable in the 1990s: the casual weekend trips to Bangkok and Dubai (so routine it is difficult to get a business class flight out on a Thursday I am reliably told); the highest-end designer kit and lavish entertainments broadcast to the world on social media; the multimillion dollar "investments" abroad.

Signs that this concentration of extreme wealth is maturing also include philanthropic foundations that support fine arts and culture; the next-gen elite are educated at the Ivy League and Oxbridge. These more elevated modes of elite status production seek to distinguish the old moneyed from those more recently arrived, and to position them in global elite circuits.

Growing inequality was visible before and played its part in the youth-led uprising of 2024. We are used to worrying about how rising inequality is viewed from below.6 But how do those at the top of the pile see the situation -- and their role in it?

We don’t know the answer to this question, but we can make some educated guesses.

One thing that has changed is that this new and newly self-conscious class of the rich has fewer and weaker affinities with the rural majority than the elites of previous generations.

Some retain interests in the agrarian economy, but the agro-processing industry in which the rich are likely to invest is little like the quasi-feudal zamindar system of the past, or the more recent relationships of distanced patronage between the nation’s rich in the cities and the precarious smallholders and the landless proletariat in the countryside.

Even if you derive your income from the agriculture sector that may no longer bring you in close contact with those who till and plough and harvest for their living.

Instead of visiting one’s village bari like the city rich once did, nowadays the affluent are more likely to retreat to bagan baris in the urban hinterlands, homes with few links to their ancestral roots, but which provide respite and private leisure beyond prying Dhaka eyes, nodding to the quieter tastes of old money and the cleaner air and relative quiet that new money can buy.

World-class levels of wealth distance the wealthy ever further from the struggles of rural life in one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable places, and I wonder if this explains why climate features prominently in the themes of elite art festivals -- a recognition of an existential threat, and a desire to aestheticise its understanding.7

However they learn about the lives of the less fortunate, today’s elites know less or less directly of how the majority live than those of yesterday, and there are no reasons to believe that direction of travel will reverse.

While growing wealth has meant growing distance, the imperatives of economic growth and development and of at least a modicum of protection for the most vulnerable remain in place, perhaps, at least for now. But this is only because they have not yet been tested by these more straitened times, the tighter fiscal space, and the pressing need to seek alternative sources of development and investment finance with which the next government will have to contend.

We already saw what happened in the latter part of Sheikh Hasina’s ill-fated recent regime, when the government proved unable to protect citizens from the economic mismanagement and inflationary crisis induced by COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; it seems clear that one reason the July uprising grew so large is that a large majority were suffering from high inflation, and the government was unable or unwilling to extend more social protection, even while the very rich grew visibly richer.

Now that international aid from the familiar OECD sources is in terminal decline, efforts to mobilize domestic revenue will accelerate, which will not make the chronically tax-dodging elite happy.

Those whose elite status depends on their professional expertise and positions will, by contrast, support a stronger effort to tax the wealth that more usually slips out of the revenue net. But we can expect that emptier coffers will push ruling parties into uncomfortable positions that contending elites will be happy to politicise against them.

While they have arguably become more distant and less interdependent with the rural majority than in previous generations, those with power and influence in the present depend far more than before for their economic success on the labour of the low-income majority -- as indeed does the economy as a whole.

The Ready Made Garment sector was smaller, less prosperous and less prominent in politics and policy in the 1990s, accounting for around $4 billion in export earnings and around 75% of GDP in the late 1990s compared to its peak of $42 bn and 82% of GDP in 2021-22.8

Around two-thirds of the members "elected" to the final parliament of the Hasina regime were businessmen, including 18 garments manufacturers; many were also members of parliamentary oversight committees for sectors in which they had direct business interests.9

It is no secret that Bangladesh’s RMG sector, despite improvements in safety and moves up the value chain, remains dependent on its access to a cheap and non-unionized labour force. Efforts to empower the nation’s garments workers have for three decades foundered on the plain fact that powerful people oppose trade unions. We should not expect meaningful improvements in industrial labour rights given the likely continuing influence of the flagship garments industry’s leaders.

The successful July uprising brought new faces into the ranks of the political elite, including young veterans of the movement with a passion for restoring democracy and cleaning up politics. There are signs that the new National Citizens Party leaders want and need to connect with the majority in the smaller cities and villages across the country. They may yet inject fresh ideas and revitalize political culture for a generation who have never experienced democracy at all.

It is too early to say how powerful they will remain as the next political settlement takes shape, or even what their policy agendas will prove to be. The student leadership of this new force has shown an interest in restoring Bengali Muslim identity, displaying some hostility to the secular liberal-progressive values of the now much-derided sushil shomaj.

Tactical alliances (if that is what they are) with Islamists are already questioning the longstanding consensus on the need to move towards gender equality and women’s empowerment. This neo-traditionalism is at odds with the prevailing mood in the 1990s, when even religious leaders grudgingly acknowledged that many women had to be able to undertake paid work for their and their families’ survival.

The move out of extreme poverty may also have removed this latitude, and in a context of high male unemployment, may be used to justify social or policy shifts against the empowerment of Bangladeshi women. We can anticipate the global culture wars and the rise of far-right ideologies to poison the elite politics of gender here, as they have elsewhere.

How those in positions of power and influence think about the existential threat Bangladesh faces from the climate crisis is something we can only guess at: to date I have seen no serious study of the elite politics of climate change in Bangladesh, despite the rich body of work on how those at the sharp end are experiencing the crisis. (Please enlighten me if you know of such work.)

The likelihood of catastrophic climate-related events should terrify us all, but many among the contemporary Bangladeshi elite have the finances and the passports to escape from or otherwise protect themselves against such disasters. No doubt the extensive investment in overseas assets is part of the elite strategy for hedging against the climate crisis. What does the possibility of exit mean for elite support for concerted action to protect those without the means to flee?

Competition or Consensus?

Why does any of this matter? One reason is that a degree of elite consensus on the policy priorities of the nation may be necessary for sustained investment and reform. A kind of agreement about the policy essentials prevailed among those with positions of power and influence in the years in which Bangladesh’s particular model of relatively inclusive development took off.

Will anything like such a consensus be possible for the even more intractable and complex challenges ahead? It is hard to say, but there are reasons to believe there will be no such "elite bargain" as we enter the second quarter of this turbulent century.

Elite consensus may not be enough to drive policies through: political leadership and state capacity will always be necessary. But deep division and politicized difference may be enough to block, for instance, urgent investments to mitigate the effects of climate change; they may make it politically costly for the ruling party to protect women or minorities from politicized religion, or workers from wage or other rights violations.

There will always be those who will do their utmost to stop political or judicial reforms that expose them to accountability. It is not clear yet where the areas of consensus might lie, but as the elite men of the National Consensus Commission have already found, there are plenty of disagreements over core policy issues.

The forthcoming election will reshuffle the elite, enlisting some new recruits to its ranks, and confirming the exile or eviction of others.That is what elections do. But elections can do other things too, and may yet be an arena for the forging of new areas of consensus, clarifying what issues matter to the masses of the electorate.

Citizens’ wishes will be of great currency for smaller and newer parties without big coffers than for the big beasts, only one of which be competing. But will this matter to those few with disproportionate power or influence, for many of whom exit is as realistic an option as voice or loyalty?

References:

[1] This is out of print now, but I found some enterprising person had posted a pdf of it here.

[2] Alamgir’s book is also out of print, and not easily found. https://www.academia.edu/82122833/Famine_in_South_Asia_Political_economy_of_mass_starvation

[3] https://www.transparency.org.uk/news/returning-bangladeshs-missing-billions. Accessed June 15, 2025.

[4] https://thehometrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Wealth-X_A-Decade-of-Wealth_May-2020.pdf. Accessed June 15 2025.

[5] I should note it is not clear what the Altrata methodology or data sources are, presumably because this is proprietorial information. See: https://wealthx.com/.

[6] https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2024/6/11/bangladeshs-missing-billionaires-a-wealth-boom-and-stark-inequality. Accessed June 15 2025.

[7] I gave a keynote speech about this in June 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4OADPgL7QTo&t=546s. See also https://www.samdani.com.bd/dhaka-art-summit.

What's Your Reaction?